Introduction

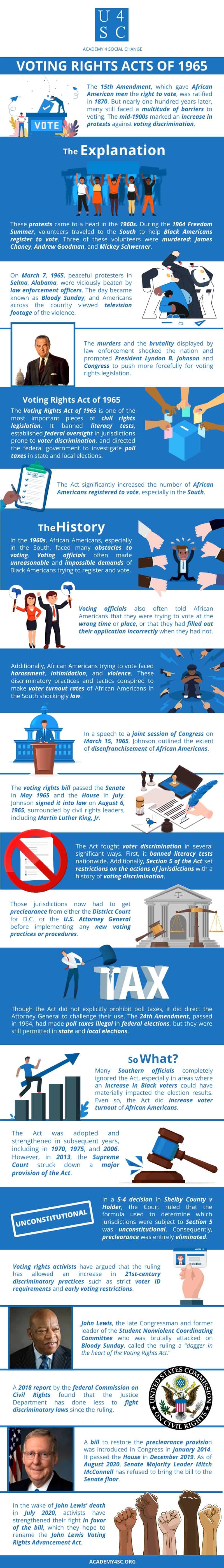

The 15th Amendment, which gave African American men the right to vote, was ratified in 1870. But nearly one hundred years later, many, especially in the South, still faced a multitude of barriers to voting. The mid-1900s marked an increase in protests against voting discrimination.

Explanation

These protests came to a head in the 1960s. During the 1964 Freedom Summer, volunteers traveled to the South to help Black Americans register to vote. Three of these volunteers were murdered: James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner. On March 7, 1965, peaceful protesters in Selma, Alabama, were viciously beaten by law enforcement officers. The day became known as Bloody Sunday, and Americans across the country viewed television footage of the violence. The murders and the brutality displayed by law enforcement shocked the nation and prompted President Lyndon B. Johnson and Congress to push more forcefully for voting rights legislation.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is one of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history. It banned literacy tests, established federal oversight in jurisdictions particularly prone to voter discrimination, and directed the federal government to investigate poll taxes in state and local elections. The Act significantly increased the number of African Americans registered to vote, especially in the South.

The History

In the 1960s, African Americans, especially in the South, faced many obstacles to voting. Voting officials often made unreasonable and impossible demands of Black Americans trying to register and vote. For example, officials gave them literacy tests designed to confuse or ask them to complete unreasonably difficult tasks like reciting the entire Constitution or explaining obscure provisions of laws. Voting officials also often told African Americans that they were trying to vote at the wrong time or place, or that they had filled out their application incorrectly when they had not.

Additionally, African Americans trying to vote faced harassment, intimidation, and violence. These discriminatory practices and tactics conspired to make voter turnout rates of African Americans in the South shockingly low. In Mississippi in 1964, for instance, only 6% of African Americans voted.

Bloody Sunday and the murders during Freedom Summer pushed President Johnson to call more forcefully for comprehensive voting rights legislation. In a speech to a joint session of Congress on March 15, 1965, Johnson outlined the extent of disenfranchisement of African Americans.

The voting rights bill passed the Senate in May 1965 and the House in July. Johnson signed it into law on August 6, 1965, surrounded by civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Act fought voter discrimination in several significant ways. First, it banned literacy tests nationwide. Additionally, Section 5 of the Act set restrictions on the actions of jurisdictions with a history of voting discrimination. Those jurisdictions now had to get preclearance from either the District Court for D.C. or the U.S. Attorney General before implementing any new voting practices or procedures. The Court or the Attorney General would ensure that the new rules did not have a discriminatory effect. Section 5 also allowed the Attorney General to decide that a county needed a federal examiner to review the qualifications of people who wanted to register. The Attorney General could also ask for federal observers to monitor a county’s polling places.

Though the Act did not explicitly prohibit poll taxes, it did direct the Attorney General to challenge their use. The 24th Amendment, passed in 1964, had made poll taxes illegal in federal elections, but they were still permitted in state and local elections.

So What?

Many Southern officials completely ignored the Act, especially in areas where an increase in Black voters could have materially impacted the election results. Even so, the Act did increase voter turnout of African Americans, in part because it gave them a way to challenge the legality of voting restrictions. For example, in Mississippi, the voter turnout of African Americans increased from 6% in 1964 to 59% in 1969. By the end of 1965, 250,000 new Black voters had been registered nationwide.

The Act was adopted and strengthened in subsequent years, including in 1970, 1975, and 2006. However, in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a major provision of the Act. In a 5-4 decision in Shelby County v Holder, the Court ruled that the formula used to determine which jurisdictions were subject to Section 5 was unconstitutional. Consequently, preclearance was entirely eliminated.

Voting rights activists have argued that the ruling has allowed an increase in 21st-century discriminatory practices such as strict voter ID requirements and early voting restrictions. John Lewis, the Congressman and former leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who was brutally attacked on Bloody Sunday, called the ruling a “dagger in the heart of the Voting Rights Act.” A 2018 report by the federal Commission on Civil Rights found that the Justice Department has done less to fight discriminatory laws since the ruling.

A bill to restore the preclearance provision was introduced in Congress in January 2014. It passed the House in December 2019. As of August 2020, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has refused to bring the bill to the Senate floor. In the wake of John Lewis’ death in July 2020, activists have strengthened their fight in favor of the bill, which they hope to rename the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.