Have You Ever?

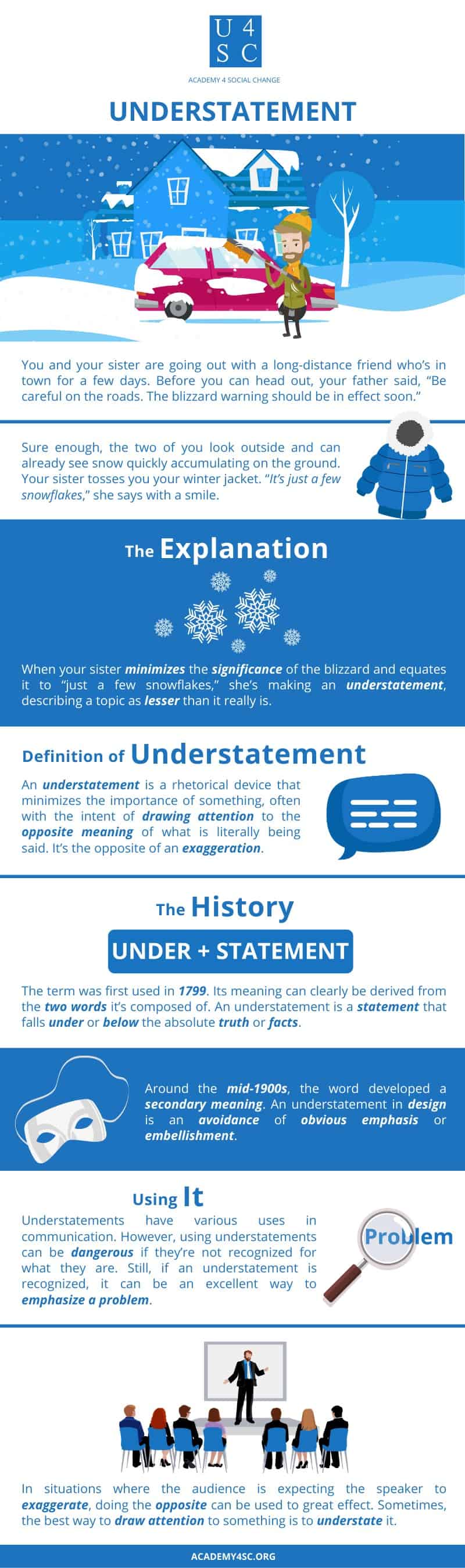

You and your sister are very excited to hang out with a long-distance friend who’s in town for a few days. Before you can head out, your father expresses some concern. “Be careful on the roads,” he says. “The blizzard warning should be in effect soon.” Sure enough, the two of you look outside and can already see snow quickly accumulating on the ground. Your sister catches you frowning and tosses you your winter jacket. “It’s just a few snowflakes,” she says with a smile.

The Explanation

When your sister minimizes the significance of the blizzard and equates it to “just a few snowflakes,” she’s making an understatement, describing a topic as lesser than it really is.

Definition of Understatement

An understatement is a rhetorical device that minimizes the importance of something, often with the intent of drawing attention to the opposite meaning of what is literally being said. It’s the exact opposite of an exaggeration.

The History

The term’s first documented use was in 1799. Its meaning can clearly be derived from the two words it’s composed of. An understatement is a statement that falls under or below the absolute truth or facts.

Around the mid-1900s, the word developed a secondary meaning. An understatement in design is an avoidance of obvious emphasis or embellishment. While this definition is very similar to its initial one, an understatement in fashion and architecture always denotes a sense of modesty, whereas understatement as a rhetorical device could serve other purposes, such as comedy.

Using It

Understatements have various uses in communication. They can be used dramatically. Think of the climactic moment of an action thriller with an intense fight scene. Our hero is fighting the bad guy only to suffer a grievous blow. The sidekick begins to fret over the profusely bleeding wound when our hero waves them away. “It’s just a scratch,” he insists, picking up his trusty weapon once more, determined to finish this final battle. The use of understatement turns the hero into a tough, stubborn, and cool rebel.

Comedy also utilizes understatements. Anyone familiar with Monty Python and the Holy Grail likely remembers the hilarious battle between Arthur and the Black Knight. Arthur quickly cuts off the knight’s arm, who insists, “Tis but a scratch” and “... I’ve had worse”. Even as the Black Knight loses his limbs, he continues to declare that he not only can still fight but also win the duel. The jarring disconnect between reality and the knight’s perception of it, along with Arthur’s growing frustration with said disconnect, is what makes the scene iconic.

Being modest and polite sometimes requires the use of understatements. When your friend asks you how you did on a test, you might not brag that you got the highest grade and instead say, “I did alright on it.” Or perhaps they spilled paint all over their backpack and are very upset about it. You might try to cheer them up by saying, “It’s really not that noticeable.” In acceptance speeches, it’s common for the speaker to use understatements out of genuine modesty or politeness.

However, using understatements can be dangerous if they’re not recognized for what they are. If a speaker has information his audience doesn’t know about, he can downplay the significance of a topic and convince his audience that a big problem is a minor inconvenience. This comes into play in politics, which is why it’s important to be informed about current events and issues so you can recognize a politician’s understatement for what it is.

Still, if an understatement is recognized, it can be an excellent way to emphasize a problem. Calling the city with the highest homicide rate, “a place with some angry neighbors,” highlights the difference between the statement and the reality of the city. It can create an air of defiance towards the status quo and the determination to change it. In situations where the audience is expecting the speaker to exaggerate, doing the opposite can be used to great effect. Sometimes, the best way to draw attention to something is to understate it.