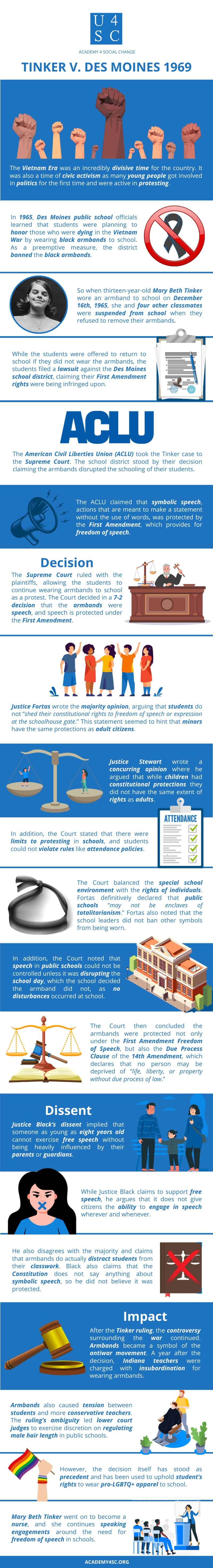

Case

The Vietnam Era was an incredibly divisive time for the country. It was also a time of civic activism as many young people got involved in politics for the first time and were active in protesting. In 1965, Des Moines public school officials learned that students were planning to honor those who were dying in the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to school. As a preemptive measure, the district banned the black armbands. So when thirteen-year-old Mary Beth Tinker wore an armband to school on December 16th, 1965, she and four other classmates were suspended from school when they refused to remove their armbands. While the students were offered to return to school if they did not wear the armbands, the students filed a lawsuit against the Des Moines school district, claiming their First Amendment rights were being infringed upon.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) took the Tinker case to the Supreme Court. The school district stood by their decision claiming the armbands disrupted the schooling of their students. The ACLU claimed that symbolic speech, actions that are meant to make a statement without the use of words, was protected by the First Amendment, which provides for freedom of speech. The Court was also asked to consider if students had the full breadth of the protections in the Bill of Rights.

Decision

The Supreme Court ruled with the plaintiffs, allowing the students to continue wearing armbands to school as a protest. The Court decided in a 7-2 decision that the armbands were speech, and speech is protected under the First Amendment. Justice Fortas wrote the majority opinion, arguing that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” This statement seemed to hint that minors have the same protections as adult citizens, though the statement was not explicit. Justice Stewart wrote a concurring opinion where he argued that while children had constitutional protections they did not have the same extent of rights as adults. By distinguishing the armband from personal appearances like clothing or hair, Fortas did not completely widen protections for minors. In addition, the Court stated that there were limits to protesting in schools, and students could not violate rules like attendance policies.

The Court balanced the special school environment with the rights of individuals. Fortas definitively declared that public schools “may not be enclaves of totalitarianism.” Fortas also noted that the school leaders did not ban other symbols from being worn, even the Nazi symbol of an iron cross. In addition, the Court noted that speech in public schools could not be controlled unless it was disrupting the school day, which the school decided the armband did not, as no disturbances occurred at school. The Court then concluded the armbands were protected not only under the First Amendment Freedom of Speech, but also the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, which declares that no person may be deprived of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” Tinker was known for establishing that students held constitutional rights at public schools that educators and school officials cannot infringe upon without due reason.

Dissent

Justice Black’s dissent implied that someone as young as eight years old cannot exercise free speech without being heavily influenced by their parents or guardians. While Justice Black claims to support free speech, he argues that it does not give citizens the ability to engage in speech wherever and whenever. His dissent goes on to say that students and teachers do not have the same freedom of speech as citizens in other spaces. He also disagrees with the majority and claims that armbands do actually distract students from their classwork. Black also claims that the Constitution does not say anything about symbolic speech, so from a strict textualist approach, he did not believe it was protected.

Impact

After the Tinker ruling, the controversy surrounding the war continued. Armbands became a symbol of the antiwar movement. A year after the decision, Indiana teachers were charged with insubordination for wearing armbands. Armbands also caused tension between students and more conservative teachers. The ruling’s ambiguity led lower court judges to exercise discretion on regulating male hair length in public schools. However, the decision itself has stood as precedent and has been used to uphold student’s rights to wear pro-LGBTQ+ apparel to school. Mary Beth Tinker went on to become a nurse, and she continues speaking engagements around the need for freedom of speech in schools.