The Problem

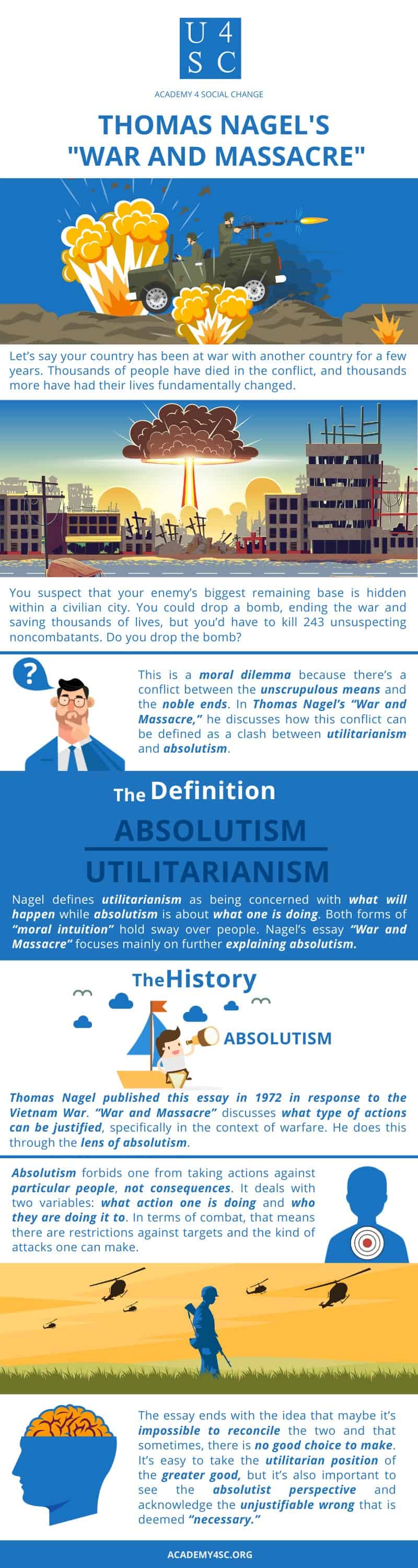

Let’s say your country has been at war with another country for a few years. Thousands of people have died in the conflict, and thousands more have had their lives fundamentally changed. Both sides are beginning to run out of resources.

You suspect that your enemy’s biggest and strongest remaining base is hidden within a civilian city. You could drop a bomb on the area, ending the war and saving thousands of lives, but you’d have to kill 243 unsuspecting noncombatants. Do you drop the bomb?

The Reason

This is considered a moral dilemma because there’s a conflict between the unscrupulous means and the noble ends. In Thomas Nagel’s “War and Massacre,” he discusses how this conflict can be defined as a clash between utilitarianism and absolutism.

The Definition: Absolutism vs. Utilitarianism

Nagel defines utilitarianism as being mainly concerned with what will happen. Absolutism, on the other hand, is about the actions one is performing, or, more simply, what one is doing. Both forms of “moral intuition” hold sway over people, which is what makes their clashing so problematic. Thomas Nagel’s essay “War and Massacre” focuses mainly on further explaining absolutism since he believes it’s not as well understood as utilitarianism.

The History

Thomas Nagel published this essay in 1972 in response to the Vietnam War. “War and Massacre” discusses what type of actions can be justified, specifically in the context of warfare. He does this through the lens of absolutism.

It’s important to understand that absolutism forbids one from taking particular actions against particular people, not particular consequences. After all, there can be unintended consequences to any action. Therefore, absolutism deals with two variables that one can clearly know: what action one is doing and who they are doing it to. In terms of combat, however, that means there are restrictions against targets and the kind of attacks one can make. This is what makes some fights clean and some tactics dirty.

Hostile treatment can never be justified against an innocent target, which is a person who is harmless. If one does not pose a direct threat, they are innocent. For this reason, it is never justifiable to attack non-combatants.

A hostile action can only ever be justified if the act still treats the target as an individual person. The action taken against the individual must be directly aimed at said individual. In Nagel’s own words, “[the act] should manifest an attitude to him [the recipient] rather than just to the situation, and he [the recipient] should be able to recognize it [the act] and identify himself as its object.”

For example, under absolutism, it would be justifiable to kill the armed combatant in front of you. He presents a direct danger, and you’re taking direct action against him. You would not be justified, though, if you attacked the man’s family standing a few feet away from him in order to distract and thus more easily kill him. His family poses no danger, so you’re not taking direct action against your true target of hostilities, and you’re using individuals as a means to an end.

So What?

Nagel defines what actions can be justified in a war, not what actions are morally correct. Nor does he state that unjustified actions should not or are not taken. After all, utilitarianism can justify many acts that absolutism condemns. In the original example, a utilitarian would sacrifice a few innocents to save thousands more.

Nagel’s essay ends with the idea that maybe it’s impossible to reconcile the two and that sometimes, through no fault of one’s own, there is no good choice to make. Even still, “War and Massacre” is an important essay because it forces us to reevaluate war without falling into the usual rhetoric. While some bad options need to be pursued, that doesn’t suddenly make them morally okay. It’s easy to take the utilitarian position of the greater good, but it’s just as important to see through the absolutist perspective and acknowledge the unjustifiable wrong that is deemed “necessary.”