Background

The Roman Republic began in 509 B.C. after Rome’s last king, Tarquinius Superbus, was expelled from the city. This event resulted from a number of abuses, the most prominent of which was the assault of the king’s son, Sextus, on Lucretia, the wife of an elite Roman. In place of the king, political offices, called magistracies, were created and held by the Roman elite to govern Rome.

Explanation

After the end of the Roman monarchy, the many magistracies that were created developed into a rigid hierarchy of political offices, each with different requirements, responsibilities, and privileges. Elite Roman men pursuing political careers tried to work their way up this highly competitive political hierarchy in order to gain more prestige and power. The highest annually elected office in Rome was that of the consul, held by two men each year. In addition to Rome’s various magistrates, there was a powerful advisory body called the senate, as well as citizen assemblies that elected officeholders and voted on proposed laws, trials, and military decisions.

The Roman Republic

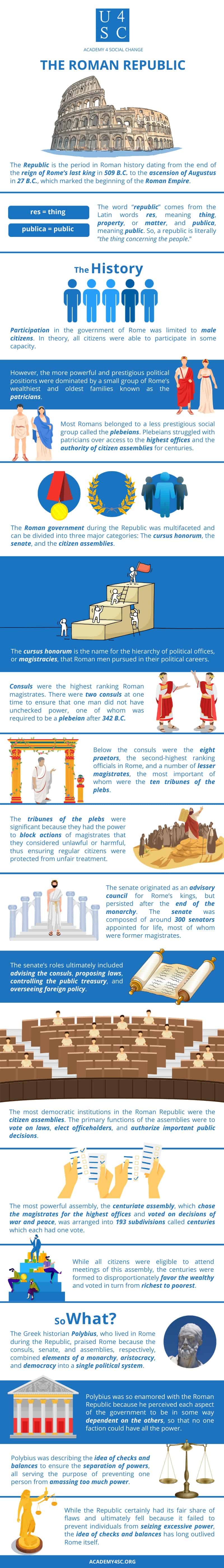

The Republic is the period in Roman history dating from the end of the reign of Rome’s last king in 509 B.C. to the ascension of Augustus in 27 B.C., which marked the beginning of the Roman Empire.

The word “republic” comes from the Latin words res, meaning thing, property, or matter, and publica, meaning public. So, a republic is literally “the thing concerning the people.”

The History

Participation in the government of Rome was limited to male citizens. In theory, all citizens were able to participate in some capacity. However, the more powerful and prestigious political positions were dominated by a small group of Rome’s wealthiest and oldest families known as the patricians. Most Romans belonged to a less prestigious social group called the plebeians. Plebeians struggled with patricians over access to the highest offices and the authority of citizen assemblies for centuries.

The Roman government during the Republic was multifaceted and can be divided into three major categories: the cursus honorum, the senate, and the citizen assemblies. The cursus honorum is the name for the hierarchy of political offices, or magistracies, that Roman men pursued in their political careers. The cursus honorum was like a ladder that politicians competed to climb, with each rung bringing increased fame, honor, power, and wealth, which culminated in the consulship, an office held by only two citizens each year.

Consuls were the highest ranking Roman magistrates and their duties included presiding over the senate and leading armies on military campaigns. There were two consuls at one time to ensure that one man did not have unchecked power, one of whom was required to be a plebeian after 342 B.C. Below the consuls were the eight praetors, the second-highest ranking officials in Rome, and a number of lesser magistrates, the most important of whom were the ten tribunes of the plebs. The tribunes of the plebs were significant because they had the power to block actions of magistrates that they considered unlawful or harmful, thus ensuring regular citizens were protected from unfair treatment. Over time, tribunes of the plebs accumulated the authority to propose legislation, summon citizens to vote, and call meetings of the senate.

While the consuls were the highest ranking officials in the Republic, the senate had the most influence and prestige. The senate originated as an advisory council for Rome’s kings, but persisted after the end of the monarchy. The senate was composed of around 300 senators appointed for life, most of whom were former magistrates. The role of the senate was first and foremost to advise, but over time it assumed a more active role in the Republic. The senate’s roles ultimately included advising the consuls, proposing laws, controlling the public treasury, and overseeing foreign policy. Furthermore, the senate possessed such tremendous influence due to the collective prestige, wealth, and experience of its members that it was extremely rare for a magistrate to act against the wishes of the senate. Opposing the senate could have disastrous consequences for a politician’s career.

The most democratic institutions in the Roman Republic were the citizen assemblies. The primary functions of the assemblies were to vote on laws, elect officeholders, and authorize important public decisions. However, these assemblies were not completely democratic. The most powerful assembly, the centuriate assembly, which chose the magistrates for the highest offices like consul and praetor and voted on decisions of war and peace, was arranged into 193 different subdivisions called centuries which each had one vote. A century’s vote was determined by a majority of its members. While all citizens were eligible to attend meetings of this assembly, the centuries were formed to disproportionately favor the wealthy and voted in turn from richest to poorest. Essentially, a rich man’s vote counted more than a poor man’s vote. Since the majority of citizens, who were also the poorest, were all grouped into the last few centuries, they often would not even get to vote at all before a majority of centuries was reached and voting ended.

So What

The Greek historian Polybius, who lived in Rome during the Republic, praised Rome because the consuls, senate, and assemblies, respectively, combined elements of a monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy into a single political system. Polybius was so enamored with the Roman Republic because he perceived each aspect of the government to be in some way dependent on the others, so that no one faction could have all the power. Polybius was describing the idea of checks and balances to ensure the separation of powers. Term limits, age requirements, the election of two consuls instead of one, and the ability of magistrates to veto each other, to name a few examples, all served the purpose of preventing one person from amassing too much power. While the Republic certainly had its fair share of flaws and ultimately fell because it failed to prevent individuals from seizing excessive power, the idea of checks and balances has long outlived Rome itself. In many modern governments, such as the United States, the legacy of the Republic lives on today.