Background

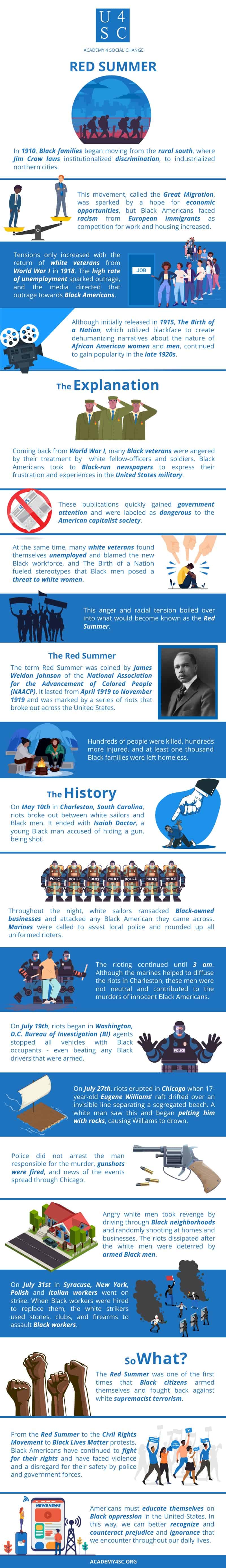

In 1910, Black families began moving from the rural south, where Jim Crow laws institutionalized discrimination, to industrialized northern cities. This movement, called the Great Migration, was sparked by a hope for economic opportunities, but Black Americans faced racism from European immigrants as competition for work and housing increased. Tensions only increased with the return of white veterans from World War I in 1918. The high rate of unemployment sparked outrage, and the media directed that outrage towards Black Americans.

Although initially released in 1915, The Birth of a Nation, which utilized blackface to create dehumanizing narratives about the nature of African American women and men, continued to gain popularity in the late 1920s. African American citizens protested the anti-Black rhetoric, but this film continued to be praised across the United States.

The Explanation

Coming back from World War I, many Black veterans were angered by their treatment by white fellow-officers and soldiers. Black Americans took to Black-run newspapers to express their frustration and depict their experiences in the United States military. These publications quickly gained government attention and were labeled as dangerous to the American capitalist society.

At the same time, many white veterans found themselves unemployed and blamed the new Black workforce, and The Birth of a Nation fueled stereotypes that Black men posed a threat to white women. This anger and racial tension boiled over into what would become known as the Red Summer.

The Red Summer

The term Red Summer was coined by James Weldon Johnson of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The Red Summer lasted from April 1919 to November 1919 and was marked by a series of riots that broke out across the United States. Hundreds of people were killed, hundreds more injured, and at least one thousand Black families were left homeless.

The History

On May 10th in Charleston, South Carolina, riots broke out between white sailors and Black men. While the cause of the riot is still unknown, it ended with Isaiah Doctor, a young Black man accused of hiding a gun, being shot. Throughout the night, white sailors ransacked Black-owned businesses and attacked any Black American they came across. Marines were called to assist local police and rounded up all uniformed rioters. The rioting continued until 3 am. Although the marines helped to diffuse the riots in Charleston, these men were not neutral and contributed to the murders of innocent Black Americans.

On July 19th, riots began in Washington, D.C. Bureau of Investigation (BI) agents stopped all vehicles with Black occupants - even beating any Black drivers that were armed. The majority of the riots were started by white sailors, marines, and soldiers. However, the BI recorded arrests of only Black Americans.

On July 27th, riots erupted in Chicago when 17-year-old Eugene Williams’ raft drifted over an invisible line separating a segregated beach. A white man saw this and began pelting him with rocks, causing Williams to drown. Police did not arrest the man responsible for the murder, gunshots were fired, and news of the events spread through Chicago. Angry white men took revenge by driving through Black neighborhoods and randomly shooting at homes and businesses. The riots dissipated after the white men were deterred by armed Black men ready to protect their families and property.

On July 31st in Syracuse, New York, Polish and Italian workers went on strike. When Black workers were hired to replace them, the white strikers used stones, clubs, and firearms to assault Black workers. Police arrived at the scene quickly to keep the riot from getting larger. After arrests were made, no other incidents occurred.

So What?

The Red Summer was one of the first times that Black citizens armed themselves and fought back against white supremacist terrorism. Black Americans returned from World War I angry. They had been told that they were fighting for democracy. Yet, the bias of the marines, popularity of racist narratives depicting Black men as dangerous, and overwhelming arrests of Black citizens shows the rampant injustice that continued to occur in the United States. The Red Summer did not signify the end of these injustices, only a time when Black Americans empowered themselves to fight against their cruel treatment.

From the Red Summer to the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter protests, Black Americans have continued to fight for their rights and have faced violence and a disregard for their safety by police and government forces. Systemic racism prevails in this country, yet many individuals remain uninformed of the United States’ racist origins and institutions. Americans must educate themselves on Black oppression in the United States. In this way, we can better recognize and counteract prejudice and ignorance that we encounter throughout our daily lives.