Introduction

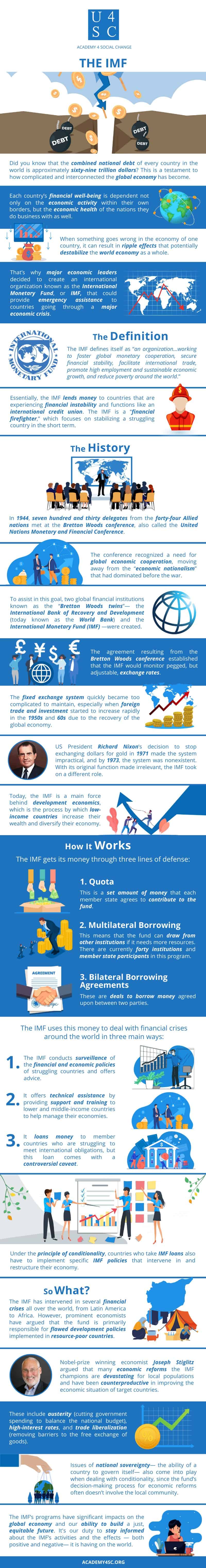

Did you know that the combined national debt of every country in the world hovers at approximately sixty-nine trillion dollars? This is a testament to just how complicated and interconnected the global economy has become. Each country’s financial well-being is dependent not only on the economic activity within their own borders, but the economic health of the nations they do business with as well. When something goes wrong in the economy of one country, it can result in ripple effects that potentially destabilize the world economy as a whole. That’s why major economic leaders decided to create an international organization that could provide emergency assistance to countries going through a major economic crisis. That international organization is known as the International Monetary Fund, or IMF.

Definition

The IMF defines itself as “an organization...working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world.” Essentially, the IMF lends money to countries that are experiencing financial instability and functions like an international credit union. Unlike the World Bank, which focuses more on long-term restructuring and development projects, the IMF is a “financial firefighter,” which focuses on stabilizing a struggling country in the short term.

History

In 1944, seven hundred and thirty delegates from the forty-four Allied nations met at the Bretton Woods conference, also called the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference. It convened the brightest minds in economics— including United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau and influential British economist John Meynard Keynes— to restructure the global economy after WWII. The conference recognized a need for global economic cooperation, moving away from the “economic nationalism” that had dominated before the war. To assist in this goal, two global financial institutions known as the “Bretton Woods twins”— the International Bank of Recovery and Development (today known as the World Bank) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) —were created.

The agreement resulting from the Bretton Woods conference established that the IMF would monitor pegged, but adjustable, exchange rates. A pegged exchange rate is when the value of a foreign currency is fixed to another value. This second value can be the value of another currency, or an object, such as gold. In this case, the standards by which other currencies were measured were gold and the US dollar. The fixed exchange system quickly became too complicated to maintain, especially when foreign trade and investment started to increase rapidly in the 1950s and 60s due to the recovery of the global economy. US President Richard Nixon’s decision to stop exchanging dollars for gold in 1971 made the system impractical, and by 1973, the system of fixed exchange in the developed world was nonexistent. With its original function made irrelevant, the IMF took on a different role.

Today, the IMF is a main force behind development economics, which is the process by which low-income countries increase their wealth and diversify their economy.

How It Works

The IMF gets its money through three lines of defense. The first is a quota that is assigned to each country based on its relative position in the world economy. This quota is a set amount of money that each member state agrees to contribute to the fund. Currently, the fund’s three biggest contributors are the United States, Japan, and China. The second is multilateral borrowing, which means that the fund can draw from other institutions if it needs more resources. There are currently forty institutions and member state participants in this program, including Belgium, Canada, and Deutsche Bank. They stand ready to lend the IMF more money if a problem occurs in the international monetary system. The third line of defense is bilateral borrowing agreements, which are deals to borrow money agreed upon between two parties.

The IMF uses this money to deal with financial crises around the world in three main ways. First, the IMF conducts surveillance of the financial and economic policies of struggling countries and offers advice. Second, it offers technical assistance by providing support and training to lower and middle-income countries to help manage their economies. Third, and most importantly, it loans money to member countries who are struggling to meet international obligations, but this loan comes with a controversial caveat. Under the principle of conditionality, countries who take IMF loans also have to implement specific IMF policies that intervene in and restructure their economy.

So What?

The IMF has intervened in several financial crises all over the world, from Latin America to Africa. However, prominent economists have argued that the fund is primarily responsible for flawed development policies implemented in resource-poor countries. Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argued that many economic reforms the IMF champions are devastating for local populations and have been counterproductive in improving the economic situation of target countries. These include austerity (cutting government spending to balance the national budget), high-interest rates, and trade liberalization (removing barriers to the free exchange of goods). Indeed, results for IMF programs have been mixed. For example, while the IMF helped Asian countries recover quickly from the financial crisis in 1997-98, Greece and Spain were plagued with years of deep recessions and high unemployment after accepting IMF loans, and their economies still haven’t fully recovered. Issues of national sovereignty— the ability of a country to govern itself— also come into play when dealing with conditionality, since the fund’s decision-making process for economic reforms often doesn’t involve the local community.

The IMF’s programs have significant impacts on the global economy and our ability to build a just, equitable future for all. It's our duty to stay informed about the IMF’s activities and the effects — both positive and negative— it is having on the world.