Have You Ever?

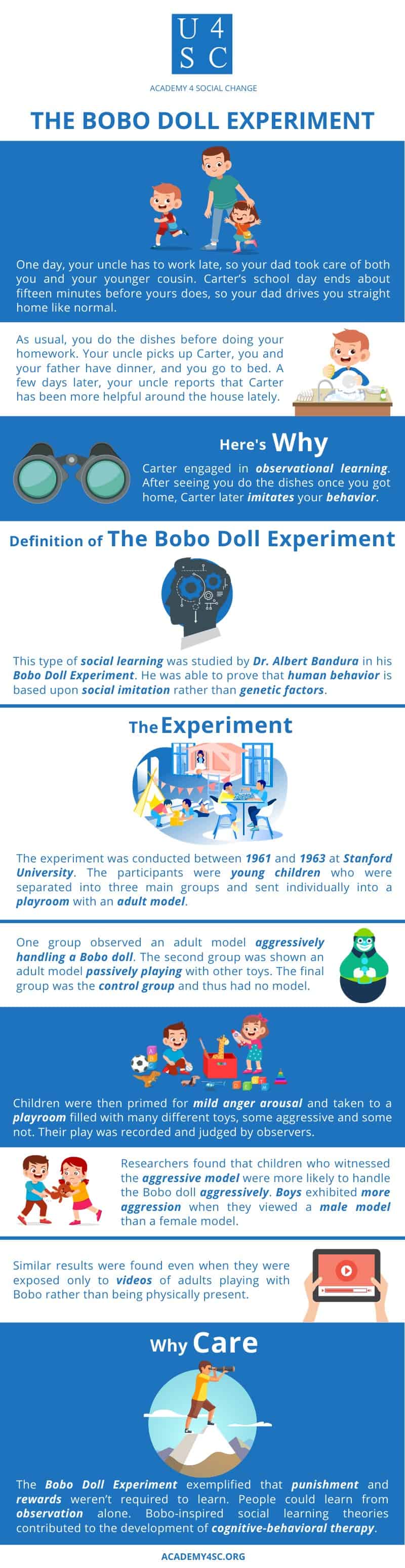

One day, your uncle has to work late, so your dad volunteers to take care of both you and your younger cousin. All in all, besides the addition of another person, your routine doesn’t change. Carter’s school day ends about fifteen minutes before yours does, so your dad drives you straight home like normal. As usual, you do the dishes before doing your homework. Your uncle picks up Carter, you and your father have dinner, and you go to bed. The day is rather uneventful. What’s interesting though is that a few days later, your uncle reports that Carter has been more helpful around the house lately. In particular, the kid has started to help put away clean dishes before starting his homework.

Here’s Why

Carter engaged in observational learning. After seeing you do the dishes once you got home, Carter later imitates your behavior.

Bobo Doll Experiment

This type of social learning was famously studied by Dr. Albert Bandura in his Bobo Doll Experiment. By having children observe an aggressive and nonaggressive model, he was able to prove that human behavior is largely based upon social imitation rather than genetic factors.

The Experiment

The experiment was conducted between 1961 and 1963 at Stanford University. The participants were young children from the university’s nursery school. They were separated into three main groups and sent individually into a playroom with an adult model. One group observed an adult model aggressively handling a Bobo doll. The second group was shown an adult model passively playing with other toys. The final group was the control group and thus had no model.

Children were then primed for mild anger arousal and taken to a playroom filled with many different toys, some aggressive (such as a toy mallet and the Bobo doll) and some not (such as a tea set or crayons). Their play was recorded and judged by observers.

Researchers found that children who witnessed the aggressive model were more likely to handle the Bobo doll aggressively. The boys of the group had an average of 38.2 derivative physical aggressions while the girls had an average of 12.7.

Boys exhibited more aggression when they viewed a male aggressive model than a female aggressive model. Specifically, the number of aggressive behaviors displayed by boys averaged 104 (male aggressive model) compared to 48.4 (aggressive female model). Similar findings were found for the girls, albeit with less drastic results. Girls averaged 57.7 when they witnessed aggressive female models compared to 36.3 when they witnessed aggressive male models.

Similar results were found even when children were exposed only to videos of adults playing aggressively or passively with Bobo rather than being physically present.

Why Care?

The Bobo Doll Experiment exemplified that punishment and rewards weren’t required to learn. People could learn from observation alone. In fact, much of how we act and behave comes from watching and learning how those around us act and behave. We’re far less likely to practice what someone preaches than what they actually perform. Bobo-inspired social learning theories contributed to the development of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Bandura’s findings were particularly relevant in America during the 60s when lawmakers, broadcasters, and the general public were debating over the effects television violence had on the behavior of children. His experiments sparked further studies not only on observational learning but on aggression- much of the debate and experiments about violent media and video games wouldn’t have happened or be happening without Dr. Bandura’s research.

Of course, it’s important to critically examine the experiment and possible limitations. The experiments never tested if the single exposure of aggression had long term effects. Children unfamiliar with the doll were found in a later experiment to be five times more likely to imitate aggressive play than those familiar with the toy, suggesting that perhaps the novelty of the Bobo doll plays a significant factor. Critics have argued that the experiment is a poor measure for actual aggressive behavior since Bobo dolls are designed to be hit and pushed around: the clown’s whole appeal is that he bounces back up after he’s hit. Like all laboratory studies, it can be argued that the results don’t necessarily translate to real world environments. Despite the shortcomings of the experiment, the Bobo doll proved to be vital to the field of psychology. The Bobo Doll experiment is one that keeps researchers “coming back for more.”