The Problem

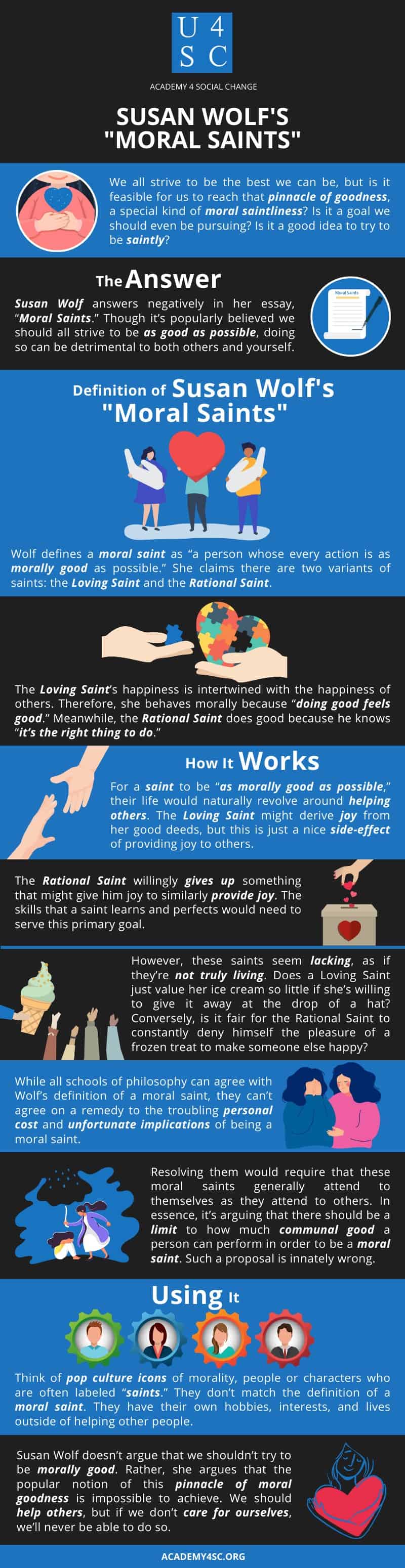

We all strive to be the best we can be, but is it feasible for us to reach that pinnacle of goodness, a special kind of moral saintliness? Furthermore, is it a goal we should even be pursuing? In essence, is it a good idea to try to be saintly?

The Answer

Susan Wolf answers negatively in her essay, “Moral Saints.” Though it’s popularly believed we should all strive to be as good as possible, doing so can be detrimental to both others and yourself.

Definition of Susan Wolf's "Moral Saints"

Wolf defines a moral saint as “a person whose every action is as morally good as possible.” She claims there are two variants of saints: the Loving Saint and the Rational Saint. The Loving Saint’s happiness is intertwined with the happiness of others. Therefore, she behaves morally because “doing good feels good.” Meanwhile, the Rational Saint does good because he knows “it’s the right thing to do.” Behaving morally doesn’t directly benefit him; in fact, most of the time, it’s a sacrifice to do so.

How It Works

These two saint models are familiar to us: they’re the fabled archetypes we’re constantly told to emulate. However, these models fall apart the closer they’re inspected.

For a saint to be “as morally good as possible,” their life would naturally revolve around helping others. The Loving Saint might derive joy from her good deeds, but this is just a nice side-effect of providing joy to others. The Rational Saint willingly gives up something that might give him joy to similarly provide joy. The skills that a saint learns and perfects would need to serve this primary goal.

Some skills and traits are incompatible with being kind and nice. Obviously, you cannot be a moral saint and be cruel to people. However, Wolf points out that there are less noticeable aspects that are incompatible with saintliness. Humor is often done at the expense of someone else or requires listeners to have some prior information, thus excluding some people. A moral saint would find this objectionable, so they would not be comedic. Similarly, they could not have a cynical or sarcastic wit. To have any of these traits would be to offend or upset someone - an action contrary to the nice nature of a saint.

In order to appease everyone, a moral saint ends up being dull and humorless. Furthermore, they can have no private lives. They cannot have hobbies or personal interests because they need to serve the community at large. Every single desire is ignored in favor of doing good for others.

This kind of lifestyle is incredibly unappealing. It’s mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausting for the person living it. Of course, it can be argued that being a moral saint shouldn’t be easy but rather difficult. It is hard for us sinful people to truly appreciate moral saints, let alone become them.

However, these saints seem lacking, as if they’re not truly living. Does a Loving Saint just value her ice cream so little if she’s willing to give it away at the drop of a hat? Conversely, is it fair for the Rational Saint to constantly deny himself the pleasure of a frozen treat to make someone else happy?

While all schools of philosophy can agree with Wolf’s definition of a moral saint, they can’t agree on a remedy to the troubling personal cost and unfortunate implications of being a moral saint. Resolving them would require that these moral saints care about their individual happiness, foster their own personal interests, and generally attend to themselves as they attend to others. However, this is applying nonmoral standards to a moral measure. In essence, it’s arguing that there should be a limit to how much communal good a person can perform in order to be a moral saint. Such a proposal is innately wrong.

Using It

Think of pop culture icons of morality, people or characters who are often labeled “saints.” They don’t match the definition of a moral saint. They have their own hobbies, interests, and lives outside of helping other people.

Wolf’s essay is important because it takes widely accepted beliefs and thoroughly investigates them. When battling these beliefs, she uses common sense and basic logic so that the people who hold them and are directly affected by them can understand her argument. Whenever you’re giving a speech or making an argument, you need to keep your audience in mind.

Susan Wolf doesn’t argue that we shouldn’t try to be morally good. Rather, she argues that the popular notion of this pinnacle of moral goodness is impossible to achieve and that we should never bemoan that fact. We should help others, but if we don’t care for ourselves, we’ll never be able to do so.