Introduction

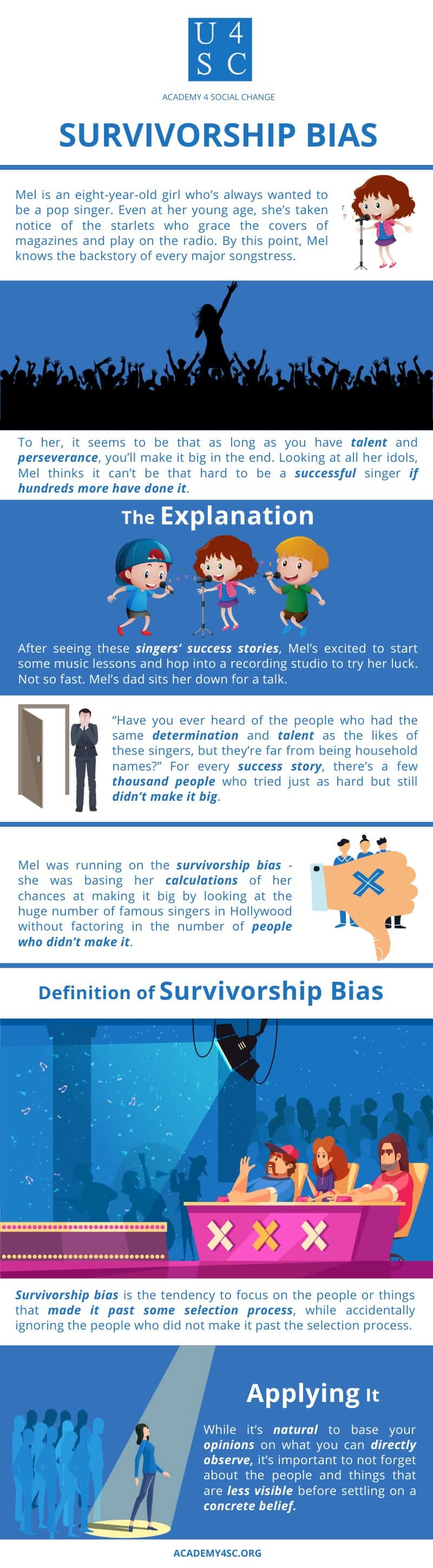

Mel is an eight-year-old girl who’s always wanted to be a pop singer. Even at her young age, she’s taken notice of the starlets who grace the covers of gossip magazines and play on the radio. By this point, Mel knows the backstory of every major songstress. Take Taylor Swift, for example: she started by mailing her demo tapes to every record company in Nashville and playing guitar in nameless bars, and now she’s selling out stadium tours! And what about Madonna? She dropped out of college and was serving pastries at Dunkin Donuts to make ends meet before she got her big break! Look at Kelly Clarkson! At just 20 years old, she won the first season of American Idol, beating out thousands of other wannabes! The moral of the story seems to be that as long as you have talent and perseverance, you’ll make it big in the end. Looking at all her idols, Mel thinks it can’t be that hard to be a successful singer if Taylor, Madonna, Kelly, and hundreds more have done it.

Here’s Why

After seeing these singers’ success stories, Mel’s excited to start some music lessons and hop into a recording studio to try her luck. Not so fast. Mel’s dad sits her down for a talk. He asks her, “Have you ever heard of Kris Allen? How about Lee DeWyze? Caleb Johnson? These are all American Idol winners who arguably had the same determination and talent as the likes of Kelly Clarkson, given that they survived multiple rounds of brutal eliminations and satisfied picky celebrity judges with their vocal abilities. But they’re far from being household names. For every success story, there’s a few thousand people like Kris Allen who tried just as hard but still didn’t make it big.

Mel is probably significantly discouraged now about her chances of becoming a major pop star. Before, she was running on the survivorship bias - she was basing her calculations of her chances at making it big solely by looking at the huge number of famous singers in Hollywood without factoring in the even bigger number of people who didn’t make it.

Survivorship Bias

Survivorship bias is the tendency to focus on the people or things that made it past some selection process, as if they are an accurate representation of the whole population, while accidentally ignoring the people who did not make it past the selection process.

The History

One of the earliest examples of the survivorship bias in action actually occurred during World War II. During the War, one of the chief concerns of the United States was finding a way to maximize the survival chances of American bomber airplane pilots. Military engineers wanted to give the planes more armor, but obviously could not cover the entire plane with this heavy material, since they would then be unable to take off. Their problem was pinpointing the parts of the plane that needed the extra protection the most.

Around this time, Abraham Wald joined a team of mathematicians who were analyzing previous aerial battles in order to help the United States’ cause. The military examined planes that safely returned from combat and provided data of where the planes were most frequently damaged. The wings, the body, and the area around the tail gunner had the most bullet holes. After considering this information, the military commanders wanted to put the armor reinforcement over those areas that had the most damage and experienced the most gunfire. But hold on.

Wald argued that these were actually the spots that need the armor the least. Why? All the planes they examined had survived in spite of all the bullet holes in the wings, the body, and around the tail gunner - these were actually the places where a plane could be shot and still function. If anything, Wald thought the engineers should add armor to the few places where the surviving planes were undamaged, because it’s highly likely that a shot to these areas would’ve brought the plane down. Wald’s crucial contribution was pointing out that the sample of planes available for damage assessment was limited to the ones that survived battle, and everyone had forgotten to consider the data presented by the planes that were shot down. Thus, Wald saved the military from falling into the trap of the survivorship bias.

Why Care?

Just because there was one successful movie made this year with a person of color as the protagonist, it doesn’t mean that Hollywood has completely overcome its racial biases or that it is easy for actors and actresses of color to find success. Just because you personally might live in a nice neighborhood doesn’t mean that the government is successfully alleviating nationwide poverty, and likewise, just because a few liberal political candidates won your state elections doesn’t mean that the Republican party is shrinking in prominence. These examples may seem like no-brainers when they’re spelled out for you.

However, when you’re going about your daily life, it’s much easier to fall into the survivorship bias as unsuccessful people and subtle social problems often escape public notice. While it’s natural to base your opinions on what you can directly observe, it’s important to not forget about the people and things that are less visible, not present in your immediate surroundings, before settling on a concrete belief.