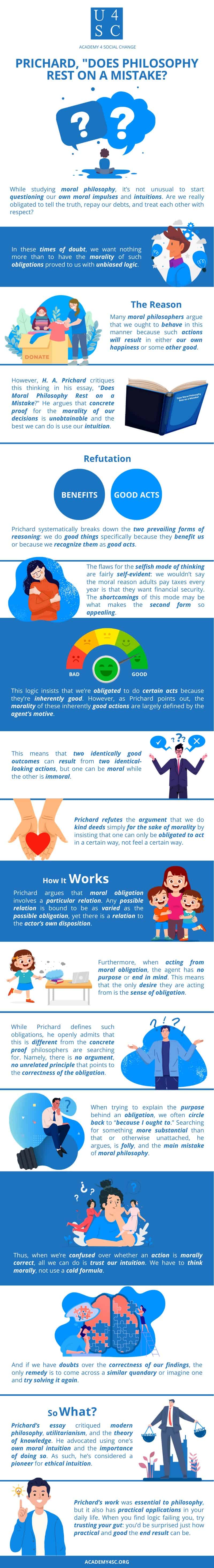

The Problem

While studying moral philosophy, it’s not unusual to start questioning our own moral impulses and intuitions. Are we really obligated to tell the truth, repay our debts, and treat each other with respect? In these times of doubt, we want nothing more than to have the morality of such obligations proved to us with unbiased logic.

The Reason

Many moral philosophers argue that we ought to behave in this manner because such actions will result in either our own happiness or some other good. However, H. A. Prichard critiques this thinking in his essay, “Does Moral Philosophy Rest on a Mistake?” He argues that concrete proof for the morality of our decisions is unobtainable and the best we can do is use our intuition.

Refutation

Prichard systematically breaks down the two prevailing forms of reasoning: we do good things specifically because they benefit us or because we recognize them as good acts. The flaws for the selfish mode of thinking are fairly self-evident: we wouldn’t say the moral reason adults pay taxes every year is that they want financial security and thus, it is right for them to do taxes. The shortcomings of this mode may be what makes the second form so appealing.

This logic insists that we’re obligated to do certain acts because they’re inherently good. However, as Prichard points out, the morality of these inherently good actions are largely defined by the agent’s motive. This means that two identically good outcomes can result from two identical-looking actions, but one can be moral while the other is immoral. Prichard refutes the argument that we do kind deeds simply for the sake of morality by insisting that one can only be obligated to act in a certain way, not feel a certain way. “Otherwise,” Prichard writes, “I should be moved towards being moved, which is impossible.”

How It Works

Prichard argues that moral obligation involves a particular relation. Any possible relation is bound to be as varied as the possible obligation, yet there is a relation to the actor’s own disposition. We are obligated to improve and modify our disposition “because we can and because others cannot directly … at least not to the same extent.” Furthermore, when acting from moral obligation, the agent has no purpose or end in mind. This means that the only desire they are acting from is the sense of obligation.

While Prichard defines such obligations, he openly admits that this is different from the concrete proof philosophers are searching for. Namely, there is no argument, no unrelated principle that points to the correctness of the obligation. When trying to explain the purpose behind an obligation, we often circle back to “because I ought to.” Searching for something more substantial than that or otherwise unattached, he argues, is folly, and the main mistake of moral philosophy.

Thus, when we’re confused over whether an action is morally correct, all we can do is trust our intuition. We have to think morally, not use a cold formula. And if we have doubts over the correctness of our findings, the only remedy is to come across a similar quandary or imagine one and try solving it again.

So What?

Prichard’s essay critiqued modern philosophy, utilitarianism, and the theory of knowledge. He advocated using one’s own moral intuition and the importance of doing so. As such, he’s considered a pioneer for ethical intuition. His work even influenced later philosophers, like John Rawls.

Prichard’s work was essential to philosophy, but it also has practical applications in your daily life. When you find logic failing you, try trusting your gut: you’d be surprised just how practical and good the end result can be.