Introduction

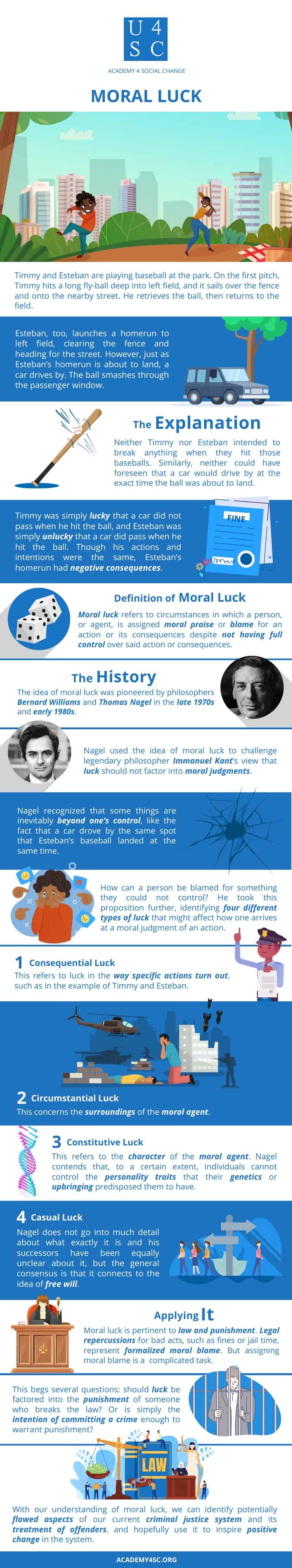

Timmy and Esteban are playing baseball at their local park. On the first pitch, Timmy hits a long fly-ball deep into left field, and it sails over the fence and onto the nearby street. He retrieves the ball, then returns to the field to pitch to Esteban. Esteban, too, launches a homerun to left field, clearing the fence and heading for the street. However, just as Esteban’s homerun is about to land, a car drives by. The ball smashes through the passenger’s window, causing $100 worth of damage. Timmy and Esteban both hit the ball to the same area, but due to circumstances beyond their control, only Esteban broke a window. Should Esteban face blame for what happened?

Explanation

Neither Timmy nor Esteban intended to break anything when they hit those baseballs. Similarly, neither could have foreseen that a car would drive behind left field at the exact time the ball was about to land. Timmy was simply lucky that a car did not pass when he hit the ball, and Esteban was simply unlucky that a car did pass when he hit the ball. Though his actions and intentions were the same as Timmy’s, Esteban’s homerun had negative consequences. Therefore, the driver of the car is likely to blame Esteban for the damage, while Timmy escapes without repercussions. The example of Timmy and Esteban represents a situation of moral luck.

Definition: Moral Luck

Moral luck refers to circumstances in which a person, or agent, is assigned moral praise or blame for an action or its consequences despite not having full control over said action or consequences.

The History

The idea of moral luck was pioneered by philosophers Bernard Williams and Thomas Nagel in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and it has been a widely discussed concept ever since. Nagel used the idea of moral luck to challenge legendary philosopher Immanuel Kant’s view that luck should not factor into moral judgments. Nagel recognized that some things are inevitably beyond one’s control, like the fact that a car drove by the same spot that Esteban’s baseball landed at the same time. How can a person be blamed for something they could not control? He took this proposition further, identifying four different types of luck that might affect how one arrives at a moral judgment of an action.

First is resultant luck, sometimes called consequential luck. This refers to luck in the way specific actions turn out, such as in the example of Timmy and Esteban. Nagel offers another example: a citizen must decide whether or not to lead an uprising against a violent, totalitarian regime. If the rebellion fails, the community will continue to live in deplorable conditions, and the regime is likely to kill more citizens. If they do revolt successfully, there will be incredible violence and bloodshed, but the brutal regime will be overthrown. Whether this citizen is viewed in a positive or negative light depends entirely on the results of the revolution. And due to the many factors determining the revolution’s success, that result is beyond one citizen’s control.

The second type of luck is circumstantial luck, which concerns the surroundings of the moral agent. Nagel gives the example of a German citizen moving to a different country just before World War II. Had this person remained in Germany under Hitler’s reign, they very well could have partaken in the heinous crimes that the Nazis and their supporters committed. However, since this person relocated, they are not involved in such horrible deeds. This person faces different moral judgments depending on their location in this scenario.

Third is constitutive luck, regarding the character of the moral agent. Nagel contends that, to a certain extent, individuals cannot control the personality traits that their genetics or upbringing predisposed them to have. A person may commit a morally wrong act, but only because that is how their brain is wired to react to their situation. Nagel asserts that we must consider these factors before making a moral judgment of an individual.

Nagel identifies a fourth type of luck—causal luck—but does not go into much detail about what exactly it is. His successors have been equally unclear about what constitutes causal luck, but the general consensus is that it connects to the idea of free will. It seems to be similar to constitutive and circumstantial luck, as well. Essentially, agents are limited in their actions by the events that preceded them. The number and nature of the options available to an agent must be considered when assessing their moral standing.

Applying It

Moral luck is pertinent to law and punishment. Legal repercussions for bad acts, such as fines or jail time, represent formalized moral blame. But assigning moral blame is a complicated task. For example, in most legal systems, manslaughter carries a different and often lighter sentence than murder. Manslaughter is killing in self-defense or negligence, while murder indicates some level of premeditation. As a matter of an agent's constitutive luck, they may naturally react to a home invader violently, resulting in the intruder’s death. At the same time, that home invader, if successful in their intentions, may kill that homeowner as part of a plan to burglarize the house. Each situation ends with a person killing another, but the unique aspects of the scenario result in assigning each person different amounts of moral blame.

Another legal example in which moral luck plays a role is the difference between attempted crimes and completed crimes. Completed crimes are almost always punished more harshly than attempted ones. For example, a person can walk onto the street and shoot another person in the back. That would be murder. However, by some stroke of luck, the intended victim might be wearing a bulletproof vest on that particular day. The shooter would be punished more harshly if the person they shot died rather than if they survived, even though their intention of murdering someone never changed.

This begs several questions: should luck be factored into the punishment of someone who breaks the law? Or is simply the intention of committing a crime enough to warrant punishment? Should the harshness of the punishment change depending on the circumstances of the crime? With our understanding of moral luck, we can identify potentially flawed aspects of our current criminal justice system and its treatment of offenders, and hopefully use it to inspire positive change in the system.