Introduction

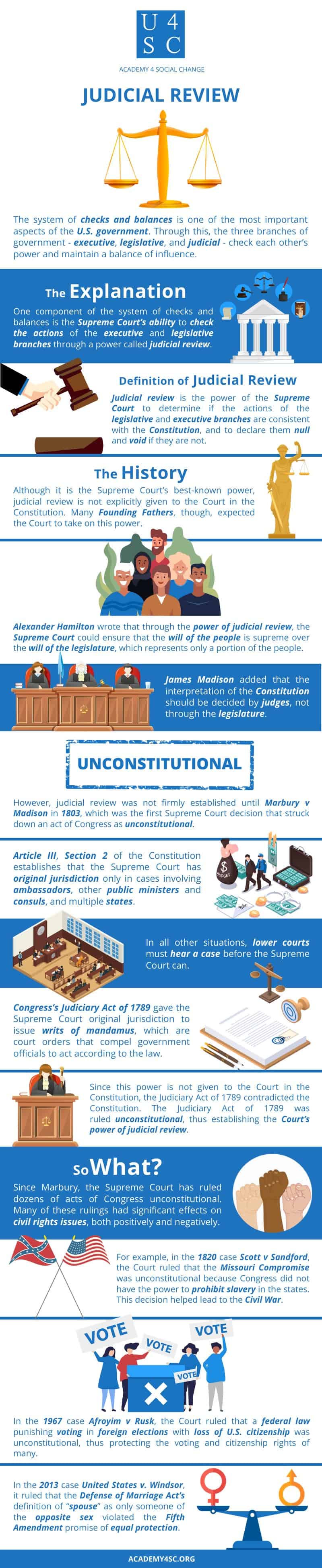

The system of checks and balances is one of the most important aspects of the U.S. government. Through this system, the three branches of government - executive, legislative, and judicial - check each other’s power and maintain a balance of influence.

Explanation

One component of the system of checks and balances is the Supreme Court’s ability to check the actions of the executive and legislative branches through a power called judicial review.

Definition

Judicial review is the power of the Supreme Court to determine if the actions of the legislative and executive branches are consistent with the Constitution, and to declare them null and void if they are not.

The History

Although it is the Supreme Court’s best-known power, judicial review is not explicitly given to the Court in the Constitution. Many Founding Fathers, though, expected the Court to take on this power; for instance, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison discussed the importance of judicial review in the Federalist Papers. Hamilton wrote that through the power of judicial review, the Supreme Court could ensure that the will of the people, which is represented through the Constitution, is supreme over the will of the legislature, which might represent only a portion of the people. Madison added that the interpretation of the Constitution should be decided by judges, not through the legislature.

However, judicial review was not firmly established until Marbury v Madison in1803, which was the first Supreme Court decision that struck down an act of Congress as unconstitutional. In the Marbury decision, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional because it expanded the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction beyond what is specified in the Constitution. The Court has original jurisdiction over a case if it can hear the case without it going through lower courts first. Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution establishes that the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction only in cases involving ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and multiple states. In all other situations, lower courts must hear a case before the Supreme Court can.

Congress’s Judiciary Act of 1789 gave the Supreme Court original jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus, which are court orders that compel government officials to act according to the law. Since this power is not given to the Court in the Constitution, the Judiciary Act of 1789 contradicted the Constitution. Article VI of the Constitution establishes it as the supreme law of the land, so the Court ruled that an act of Congress contrary to the Constitution must be struck down. It ruled the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutional, thus establishing the Court’s power of judicial review.

So What?

Since Marbury, the Supreme Court has ruled dozens of acts of Congress unconstitutional. Many of these rulings had significant effects on civil rights issues, both positively and negatively. For example, in the 1820 case Scott v Sandford, the Court ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional because Congress did not have the power to prohibit slavery in the states. This decision enraged Northerners and helped lead to the Civil War. Other rulings have helped advance civil rights causes. In the 1967 case Afroyim v Rusk, the Court ruled that a federal law punishing voting in foreign elections with loss of U.S. citizenship was unconstitutional, thereby protecting the voting and citizenship rights of many. More recently, the Court used judicial review to protect the rights of same-sex couples. In the 2013 case United States v. Windsor, it ruled that the Defense of Marriage Act’s definition of “spouse” as only someone of the opposite sex violated the Fifth Amendment promise of equal protection.