The Problem

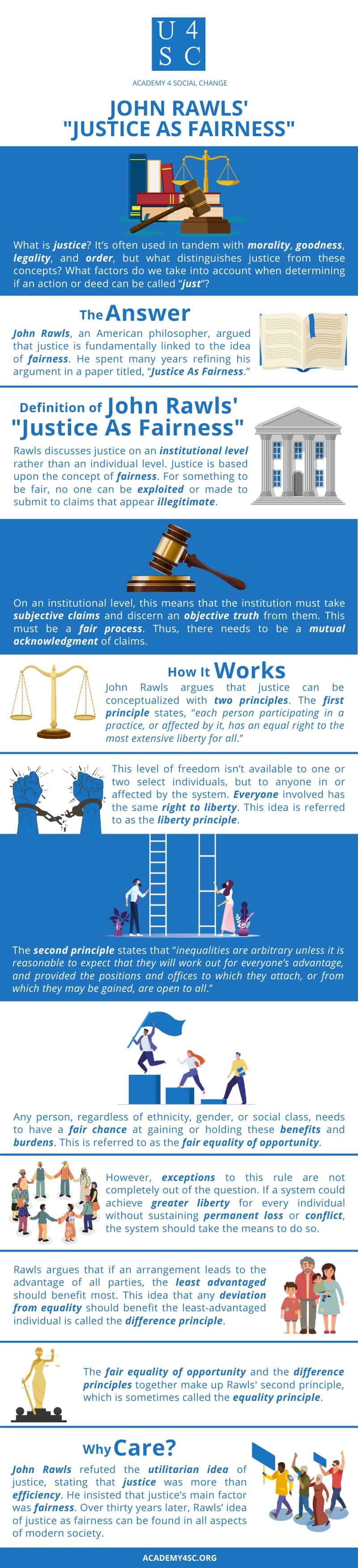

What is justice? It’s often used in tandem with morality, goodness, legality, and order, but what distinguishes justice from these concepts? What factors do we take into account when determining if a course of action or past deed can accurately be called “just”?

The Answer

John Rawls, an American philosopher, argued that justice is fundamentally linked to the idea of fairness. He spent many years refining his argument in a paper titled, “Justice As Fairness.”

Definition of John Rawls' "Justice As Fairness"

Rawls discusses justice on an institutional rather than an individual level. Justice is based upon the concept of fairness. For something to be fair, no one can be exploited or made to submit to claims that appear illegitimate.

In practice at an institutional level, this means that the institution must take subjective claims and discern an objective truth from them. This must be a fair process: there needs to be a balance between competing claims. Thus, in order to be just, there needs to be a mutual acknowledgment of claims.

How It Works

John Rawls argues that justice can be conceptualized with two principles. The first principle states, “each person participating in a practice, or affected by it, has an equal right to the most extensive liberty for all.” This means those people should have as much freedom as possible, provided that their freedom doesn’t trample on the freedom of others in or affected by the system. It’s important to remember that this level of freedom isn’t available to one or two select individuals, but to anyone in or affected by the system. Everyone involved has the same right to liberty. This idea is referred to as the liberty principle.

The second principle states that “inequalities are arbitrary unless it is reasonable to expect that they will work out for everyone’s advantage, and provided the positions and offices to which they attach, or from which they may be gained, are open to all.” This statement reveals that, as a rule, inequalities are not allowed. Any person, regardless of ethnicity, gender, or social class, needs to have a fair chance at gaining or holding these benefits and burdens. Thus, the only way to hold such responsibilities and privileges is to win a fair competition against other contestants in which one is judged on their merits. This idea that any position or office must be open to any individual provided that they can prove their merit in fair competition is referred to as the fair equality of opportunity.

However, exceptions to this rule are not completely out of the question. If a system could achieve greater liberty for every individual without sustaining permanent loss or conflict, the system should take the means to do so: doing otherwise would be irrational. Thus, inequalities can occasionally be tolerated, provided such exceptions can be justified. Any justification needs to be proved by those wishing to break from the rule of equal liberty, not the practice itself.

For example, say that your parents will let you and your siblings use the spare car on Saturdays if you complete some big chores around the house by the end of the month. You suggest to your older siblings that you split the chores up equally. However, they’re hesitant to agree - your brother’s theater group has him at school late, and your sister’s debate team needs her to put in some extra hours, too. Thus, they suggest you take care of a larger chunk of the chores, but in exchange, you can decide the destination for every fourth Saturday.

In this example, you take on the temporary responsibility of a higher workload so that you and your siblings have greater freedom. Notice how this arrangement leads to the advantage of all involved parties, not just the majority. Also, you, the least advantaged in the current situation, stand to benefit the most. Rawls argues that this should always be the case when exceptions are tolerated. This idea that any deviation from equality should benefit the least-advantaged individual is called the difference principle.

The fair equality of opportunity and the difference principles together make up Rawls' second principle, which is sometimes called the equality principle. However, the equality principle is more often broken down into these two different principles for ease of reference.

Rawls also argued that like cases need to be treated alike. Practices, he said, have to “make in advance a firm commitment ...[so] that no one be given the opportunity to tailor the canons of a legitimate complaint to fit his own special condition, and then to discard them when they no longer suit his purpose.” This would help ensure that any exceptions argued would be legitimate ones since if they were successfully justified, they could easily be used against those who first proposed them.

Rawls proposes a thought experiment to explain how such a definition of justice could’ve naturally developed. He explains that people wouldn’t be mad when they see or learn that others are in better positions than themselves unless they feel that these people got these positions unfairly or they themselves were slighted. He rewrote and reworded his argument several times, but these principles consistently reappeared again and again.

Why Care?

John Rawls refuted the utilitarian idea of justice, stating that justice was more than efficiency. He insisted that justice’s main factor was fairness. Now, over thirty years later, that idea of justice is still very prevalent. We often argue whether punishments or rewards are deserved by certain individuals. We fight for equal liberty among all people. When similar cases are treated differently, we become outraged. Rawls’ idea of justice as fairness can be found in all aspects of modern society.