Introduction

One of Arkady’s classmates has been bullying other students. Arkady tells her teacher, but she ignores it, as do the principal and the superintendent. Frustrated with their unwillingness to act, she turns to the Department of Education, who listens to her and opens an investigation.

Explanation

Similarly to Arkady’s situation, the International Criminal Court is only used when countries are unwilling or unable to deal with a critical issue. The Department of Education isn’t going to start handling all the disciplinary actions of Arkady’s school. Neither is the International Criminal Court meant to serve as a substitute for the court and legal systems of individual countries. Instead, it works to address problems that affect the international community.

International Criminal Court

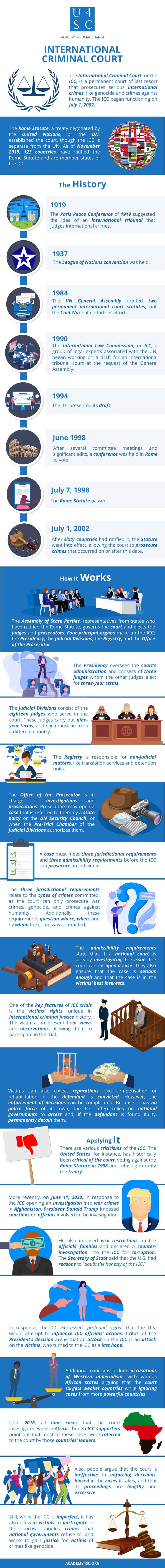

The International Criminal Court, or the ICC, is a permanent court of last resort that prosecutes serious international crimes, like genocide and crimes against humanity. The ICC began functioning on July 1, 2002. The Rome Statute, a treaty negotiated by the United Nations, or the UN, established the court, though the ICC is separate from the UN. As of November 2019, 123 countries have ratified the Rome Statute and are member states of the ICC.

The History

The idea of an international tribunal that judges international crimes is not new. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 suggested it, as did a League of Nations convention in 1937. After World War II, the Allied powers convened two tribunals to prosecute Axis leaders of war crimes. In 1948, the UN General Assembly drafted two permanent international court statutes, but the Cold War halted further efforts.

The International Law Commission, or ILC, a group of legal experts associated with the UN, began working on a draft for such a court in 1990, at the request of the General Assembly. The ILC presented its draft in 1994, and after several committee meetings and significant edits, a conference was held in Rome in June of 1998 to vote. On July 7, the Rome Statute passed. On July 1, 2002, after sixty countries had ratified it, the Statute went into effect, allowing the court to prosecute crimes that occurred on or after this date.

How It Works

The Assembly of State Parties, representatives from states who have ratified the Rome Statute, governs the court and elects the judges and prosecutors. Four principal organs make up the ICC: the Presidency, the Judicial Divisions, the Registry, and the Office of the Prosecutor. The Presidency oversees the court’s administration and consists of three judges whom the other judges elect for three-year terms. The Judicial Divisions consist of the eighteen judges who serve in the court. These judges carry out nine-year terms, and each must be from a different country. The Registry is responsible for non-judicial matters, like translation services and detention units.

The Office of the Prosecutor is in charge of investigations and prosecutions. Prosecutors may open a case that is referred to them by a state party or the UN Security Council, or when the Pre-Trial Chamber of the Judicial Divisions authorizes them to open an investigation due to information from outside sources, like individuals or organizations. All prosecutors must act independently, but critics say there are few checks on the prosecutors’ power.

A case must meet three jurisdictional requirements and three admissibility requirements before the ICC can prosecute an individual. The three jurisdictional requirements relate to the types of crimes committed, as the court can only prosecute war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity. Additionally, these requirements question where, when, and by whom the crime was committed. The admissibility requirements state that if a national court is already investigating the issue, the court cannot open a case. They also ensure that the case is serious enough and that the case is in the victims’ best interests, taking into account the gravity of the crime, the age and health of the alleged perpetrator, and their alleged role in the crime.

One of the key features of ICC trials is the victims’ rights, unique in international criminal justice history. The victims can present their views and observations, allowing them to participate in the trial. Victims can also collect reparations, like compensation or rehabilitation, if the defendant is convicted. However, the enforcement of decisions can be complicated. Because it has no police force of its own, the ICC often relies on national governments to arrest and, if the defendant is found guilty, permanently detain them.

Applying It

There are various criticisms of the ICC. The United States, for instance, has historically been critical of the court, voting against the Rome Statute in 1998 and refusing to ratify the treaty. More recently, on June 11, 2020, in response to the ICC opening an investigation into war crimes in Afghanistan, including those committed by Americans, President Donald Trump imposed sanctions on officials involved in the investigation. He also imposed visa restrictions on the officials’ families and declared a counter-investigation into the ICC for corruption. The Secretary of State said that the U.S. had reasons to “doubt the honesty of the ICC.” In response, the ICC expressed “profound regret” that the U.S. would attempt to influence ICC officials’ actions. Critics of the President’s decision argue that an attack on the ICC is an attack on the victims, who turned to the ICC as a last hope.

Additional criticisms include accusations of Western imperialism, with various African states arguing that the court targets weaker countries while ignoring cases from more powerful countries. Until 2016, all nine cases that the court investigated were in Africa, though ICC supporters point out that most of these cases were referred to the court by those countries’ leaders. Also, people argue that the court is ineffective in enforcing decisions, biased in the cases it takes, and that its proceedings are lengthy and excessive. Still, while the ICC is imperfect, it has also allowed victims to participate in their cases, handles crimes that national governments refuse to, and works to gain justice for victims of crimes like genocide.