Introduction

Morgan’s family is having issues with their neighbors leaving garbage in the hallway of their apartment building. They try to talk it out but can’t reach a solution, so they go to the apartment council. However, the council can’t settle disputes between two neighbors, and so they turn to their landlord, who hears both sides and makes a decision.

Explanation

The landlord is similar to the International Court of Justice, which settles disputes between states and rules on international law issues. Like Morgan and their neighbors, when two or more countries have a problem they cannot work out, they can turn to the International Court of Justice.

International Court of Justice

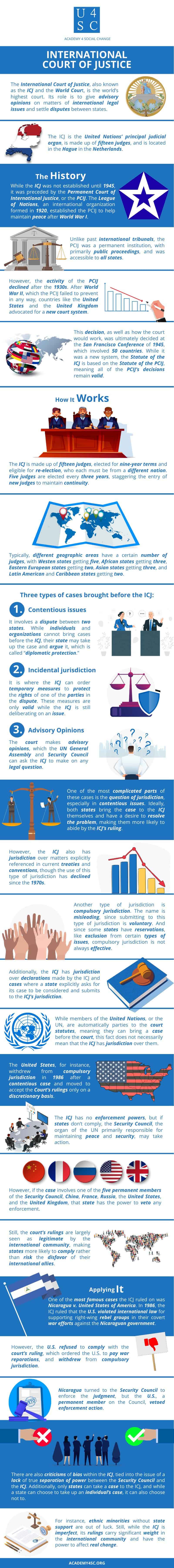

The International Court of Justice, also known as the ICJ and the World Court, is the world’s highest court. Its role is to give advisory opinions on matters of international legal issues and settle disputes between states. The ICJ is the United Nations’ principal judicial organ, is made up of fifteen judges, and is located in the Hague in the Netherlands.

The History

While the ICJ was not established until 1945, it was preceded by the Permanent Court of International Justice, or the PCIJ. The League of Nations, an international organization formed in 1920, established the PCIJ to help maintain peace after World War I. Unlike past international tribunals, the PCIJ was a permanent institution, with primarily public proceedings, and was accessible to all states.

However, the activity of the PCIJ declined after the 1930s. After World War II, which the PCIJ failed to prevent in any way, countries like the United States and the United Kingdom advocated for a new court system. This decision, as well as how the court would work, was ultimately decided at the San Francisco Conference of 1945, which involved 50 countries. While it was a new system, the Statute of the ICJ is based on the Statute of the PCIJ, meaning all of the PCIJ’s decisions remain valid.

How It Works

The ICJ is made up of fifteen judges, elected for nine-year terms and eligible for re-election, who each must be from a different nation. Five judges are elected every three years, staggering the entry of new judges to maintain continuity. Typically, different geographic areas have a certain number of judges, with Westen states getting five, African states getting three, Eastern European states getting two, Asian states getting three, and Latin American and Caribbean states getting two.

There are three types of cases brought before the ICJ. First are contentious issues, which involve a dispute between two states. While individuals and organizations cannot bring cases before the ICJ, their state may take up the case and argue it, which is called “diplomatic protection.” The second types of cases are incidental jurisdiction, where the ICJ can order temporary measures to protect the rights of one of the parties in the dispute. These measures are only valid while the ICJ is still deliberating on an issue. Thirdly, the court makes advisory opinions, which the UN General Assembly and Security Council can ask the ICJ to make on any legal question.

One of the most complicated parts of these cases is the question of jurisdiction, especially in contentious issues. Ideally, both states bring the case to the ICJ themselves and have a desire to resolve the problem, making them more likely to abide by the ICJ’s ruling. However, the ICJ also has jurisdiction over matters explicitly referenced in current treaties and conventions, though the use of this type of jurisdiction has declined since the 1970s.

Another type of jurisdiction is compulsory jurisdiction. The name is misleading, since submitting to this type of jurisdiction is voluntary. And since some states have reservations, like exclusion from certain types of issues, compulsory jurisdiction is not always effective. Additionally, the ICJ has jurisdiction over declarations made by the ICJ and cases where a state explicitly asks for its case to be considered and submits to the ICJ’s jurisdiction.

While members of the United Nations, or the UN, are automatically parties to the court statutes, meaning they can bring a case before the court, this fact does not necessarily mean that the ICJ has jurisdiction over them. The United States, for instance, withdrew from compulsory jurisdiction in 1986 after a contentious case and moved to accept the Court’s rulings only on a discretionary basis.

The ICJ has no enforcement powers, but if states don’t comply, the Security Council, the organ of the UN primarily responsible for maintaining peace and security, may take action. However, if the case involves one of the five permanent members of the Security Council, China, France, Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom, that state has the power to veto any enforcement. Still, the court’s rulings are largely seen as legitimate by the international community, making states more likely to comply rather than risk the disfavor of their international allies.

Applying It

One of the most famous cases the ICJ ruled on was Nicaragua v. United States of America. In 1986, the ICJ ruled that the U.S. violated international law for supporting right-wing rebel groups in their covert war efforts against the Nicaraguan government. However, the U.S. refused to comply with the court’s ruling, which ordered the U.S. to pay war reparations, and withdrew from compulsory jurisdiction. Nicaragua turned to the Security Council to enforce the judgment, but the U.S., a permanent member on the Council, vetoed enforcement action.

There are also criticisms of bias within the ICJ, tied into the issue of a lack of true separation of power between the Security Council and the ICJ. Additionally, only states can take a case to the ICJ, and while a state can choose to take up an individual’s case, it can also choose not to. For instance, ethnic minorities without state support are out of luck. Still, while the ICJ is imperfect, its rulings carry significant weight in the international community and have the power to affect real change.