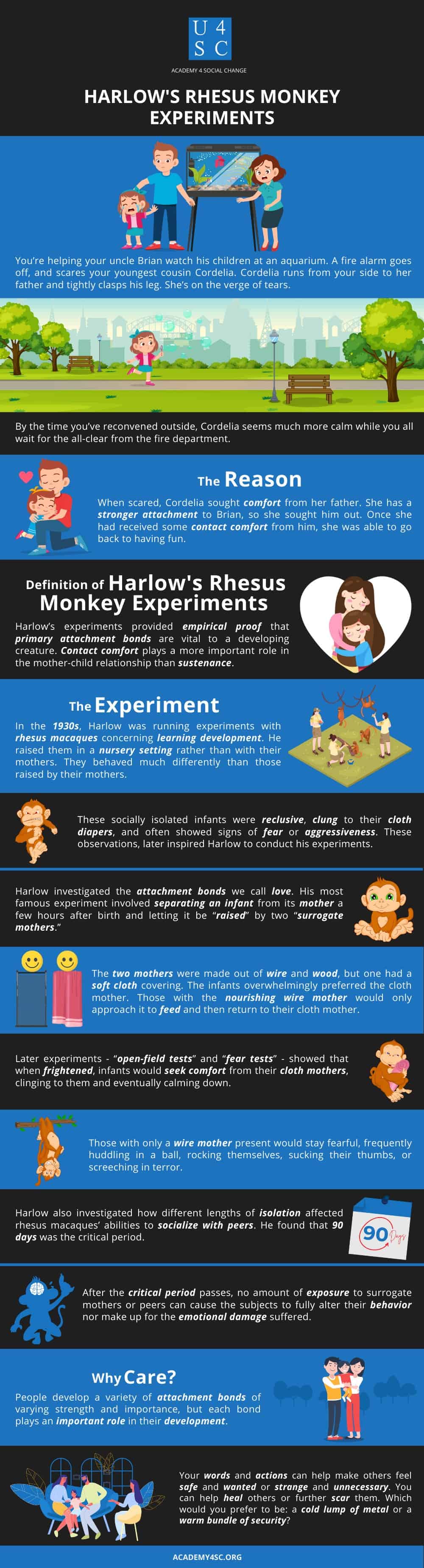

Have You Ever?

You’re helping your uncle Brian watch his children at an aquarium. A fire alarm goes off, and scares your youngest cousin Cordelia. Cordelia runs from your side to her father and tightly clasps his leg. She’s on the verge of tears. You’re not quite confident she fully understands Brian’s explanation of the fire alarm, but you don’t stick around to find out, instead seeking out the two middle schoolers who are already heading towards the nearest exit. By the time you’ve reconvened outside, Cordelia seems much more calm and is happily picking at the grass while you all wait for the all-clear from the fire department.

The Reason

When scared, Cordelia sought comfort from her father rather than you, even though you were closer. She has a stronger attachment to Brian, so she sought him out. Once she had received some contact comfort from him, she was able to go back to playing and having fun.

Harlow’s Rhesus Monkey Experiments

Harlow’s experiments provided empirical proof that primary attachment bonds are vital to a developing creature. Contact comfort plays a much more important role in the mother-child relationship than sustenance does. Furthermore, there’s a time limit for when such bonds need to be forged without causing permanent emotional, mental, and social issues.

The Experiment

In the 1930s, Harlow was running experiments with rhesus macaques concerning learning development. To this end, he chose to raise them in a nursery setting rather than with their mothers. While Harlow and his associates could care for the physical needs of the baby monkeys, there was no denying that they regularly behaved much differently than those raised by their mothers. These socially isolated infants were reclusive, clung to their cloth diapers, and often showed signs of fear or aggressiveness. These observations, along with the later growing general debate over a mother’s role in her child’s development, would inspire Harlow to conduct his famous experiments.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Harlow investigated the attachment bonds we call love with his rhesus monkeys as test subjects. His most famous experiment involved separating an infant from its mother a few hours after birth and letting it be “raised” by two “surrogate mothers.” The two mothers were made out of wire and wood, but one had a soft cloth covering. In one group, only the cloth mother had a bottle attached to it. For the other, only the wire mother provided the baby sustenance. According to the prevailing beliefs of the time, the infant should have shown an attachment for whichever mother held the bottle, but this wasn’t the case. In all groups, the infants overwhelmingly preferred the cloth mother. Those with the nourishing wire mother would only approach it to feed and then return to their cloth mother.

Later experiments - “open-field tests” and “fear tests” - showed that when frightened, infants would seek comfort from their cloth mothers, clinging to them and eventually calming down. Those without their surrogate mother or those with only a wire mother present would stay fearful, frequently huddling in a ball, rocking themselves, sucking their thumbs, or screeching in terror.

Harlow also investigated how different lengths of isolation affected rhesus macaques’ abilities to socialize with peers. Subjects were isolated for months and even years. He found that 90 days was the critical period. Subjects exhibited dramatic, debilitating behavior but, when integrated with controls of the same age, slowly started to adapt and eventually show normal behavior. After the critical period passes, no amount of exposure to surrogate mothers or peers can cause the subjects to fully alter their behavior nor make up for the emotional damage suffered. The longer subjects were isolated, the more debilitating their behavior became. In some cases, severely isolated subjects developed emotional anorexia upon reintegration with their peers and subsequently died.

Why Care?

The idea of comfort contact isn’t a radical one today, but it was during the time of Harlow’s experiments. There were a number of records and instances of human children developing poorly socially, emotionally, and psychologically as a result of what appeared to be a lack of parental attachments, but there was no hard proof. The popular opinion of the day was that parents should only care for their children’s physical needs. Cuddling was on par with coddling and was believed to cause children to become too dependent. Harlow provided the necessary evidence to dispute such beliefs via his experiments. Institutionalized child care was shown to be detrimental to children.

This is why in issues of guardian rights, the child’s preferences should be prioritized over which adult can provide the most financially. Adoption is championed as superior over other arrangements because it provides the permanence needed for attachment bonds to develop. Harlow showed that love doesn’t develop from simply caring for the physical needs of a child: it comes from providing a feeling of safety and comfort. A father can play just as critical of a role in his child’s development as the mother. You don’t need to be a biological parent to truly care for a child. An infant raised by guardians rather than their biological mother is not guaranteed to suffer from such an arrangement.

Harlow’s experiments showed that parenting and mentorship isn’t limited to adults. Peers can be instrumental in helping each other lead healthy, happy lives. People develop a variety of attachment bonds of varying strength and importance, but each bond plays an important role in their development. Your words and actions can help make others feel safe and wanted or strange and unnecessary. You can help heal others or further scar them. It’s entirely up to you, so which would you prefer to be: a cold lump of metal or a warm bundle of security?