Problem

Do you know what your voting district looks like? If you aren’t a voter, and even if you are, why would you? It doesn’t seem important—which is why most people don’t understand how these districts are manipulated to serve political interests.

Here’s Why

You can only affect election results in your own district and issues affecting the population of your district will only be addressed if inhabitants are represented fairly. But the people drawing district lines in your state may not be trying to make sure your voice is heard and your community is represented; they may be trying to manipulate the districts to decide the outcome of elections in their favor.

Definition: Gerrymandering

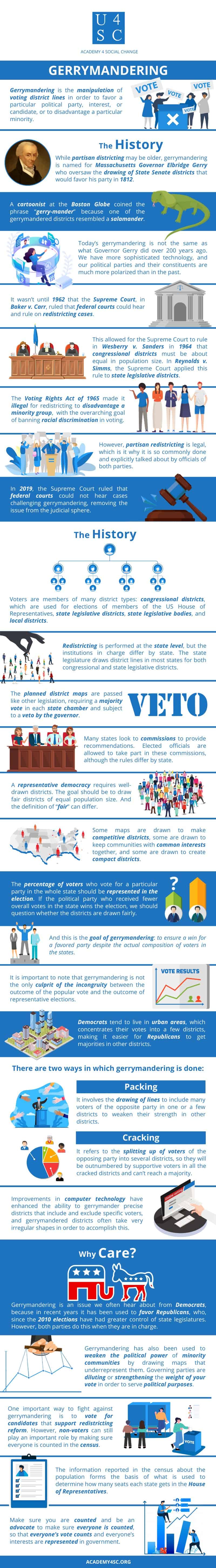

Gerrymandering is the manipulation of voting district lines in order to favor a particular political party, interest, or candidate, or to disadvantage a particular minority.

The History

While partisan districting may be older, gerrymandering is named for Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry who oversaw the drawing of State Senate districts that would favor his party in 1812. A cartoonist of the Boston Globe coined the phrase “gerry-mander” because one of the gerrymandered districts resembled a salamander. While the term may be old, today’s gerrymandering is not the same as what Governor Gerry did over 200 years ago. We have more sophisticated technology, and our political parties and their constituents are much more polarized than in the past.

It wasn’t until 1962 that the Supreme Court, in Baker v. Carr, ruled that federal courts could hear and rule on redistricting cases. This allowed for the Supreme Court to rule in Wesberry v. Sanders in 1964 that congressional districts must be about equal in population size. In Reynolds v. Simms, the Supreme Court applied this rule to state legislative districts.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 made it illegal for redistricting to disadvantage a minority group, with the overarching goal of banning racial discrimination in voting. However, partisan redistricting is legal, which is it why it is so commonly done and explicitly talked about by officials of both parties. In 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts could not hear cases challenging gerrymandering, removing the issue from the judicial sphere.

How It Works

Voters are members of many district types: congressional districts, which are used for elections of members of the US House of Representatives, state legislative districts, which are used for elections to the state legislative bodies, and local districts, which include city or town councilpeople and assembly districts.

Redistricting is performed at the state level, but the institutions in charge differ by state. The state legislature draws district lines in most states for both congressional and state legislative districts. The planned district maps are passed like other legislation, requiring a majority vote in each state chamber and subject to a veto by the governor. Connecticut and Maine require a supermajority to approve a new plan and in Connecticut, Florida, Maryland, Mississippi, and North Carolina, plans are passed through a joint resolution so a veto is not possible. In all of these states, however, it is the state legislature itself that is responsible for drawing the districts that will elect them. Many states look to commissions to provide recommendations. Arkansas, Colorado, Hawaii, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania put entities called politician commissions in charge of redistricting. Elected officials are allowed to take part in these commissions, although the rules differ by state. Unlike most of the states, Alaska, Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, and Washington use an independent commission, of which elected officials cannot be directly involved, to redistrict. Some of these states have further rules limiting the role of public and elected officials in the process.

A representative democracy requires well-drawn districts. The goal should be to draw fair districts of equal population size. And the definition of “fair” can differ. Some maps are drawn to make competitive districts, some are drawn to keep communities with common interests together, and some are drawn to create compact districts. But a fair district doesn’t favor or disadvantage a particular interest, candidate, party, or community.

The percentage of voters who vote for a particular party in the whole state should be represented in the outcome of the election. If the political party who received fewer overall votes in the state wins the election, especially by a great margin, we should question whether the districts are drawn fairly. And this is the goal of gerrymandering: to ensure a win for a favored party despite the actual composition of voters in the states. Any district can be drawn to favor one party or another. In a congressional election, this would mean that the party who got more overall votes may still have fewer seats if the congressional districts were drawn to favor the opposing party. It is important to note that gerrymandering is not the only culprit of the incongruity between the outcome of the popular vote and the outcome of representative elections. Democrats tend to live in urban areas, which concentrates their votes into a few districts, making it easier for Republicans to get majorities in other districts.

There are two ways in which gerrymandering is done: packing and cracking. Packing involves the drawing of lines to include many voters of the opposite party in one or a few districts to weaken their strength in other districts. Cracking refers to the splitting up of voters of the opposing party into several districts, so they will be outnumbered by supportive voters in all the cracked districts and can’t reach a majority.

Improvements in computer technology have enhanced the ability to gerrymander precise districts that include and exclude specific voters, and gerrymandered districts often take very irregular shapes in order to accomplish this. However, an odd shape isn’t necessarily evidence of gerrymandering. A fairly drawn district isn’t necessarily perfectly rectangular, because most of the time we don’t live in neighborhoods and communities that are regular shapes. Furthermore, there isn’t a single way to draw the district lines.

Why Care?

Gerrymandering is an issue we often hear about from Democrats, because in recent years it has been used to favor Republicans, who, since the 2010 elections have had greater control of state legislatures. However, both parties do this when they are in charge. Gerrymandering has also been used to weaken the political power of minority communities by drawing maps that underrepresent them. Governing parties are diluting or strengthening the weight of your vote in order to serve political purposes.

One important way to fight against gerrymandering is to vote for candidates that support redistricting reform. However, non-voters can still play an important role by making sure everyone is counted in the census. The information reported in the census about the population forms the basis of what is used to determine how many seats each state gets in the House of Representatives. Underfunding the census could lead to an undercount of people, especially low-income, rural, or minority populations whose votes are necessary for a fair democracy. Make sure you are counted and be an advocate to make sure everyone is counted, so that everyone’s vote counts and everyone’s interests are represented in government.