Background

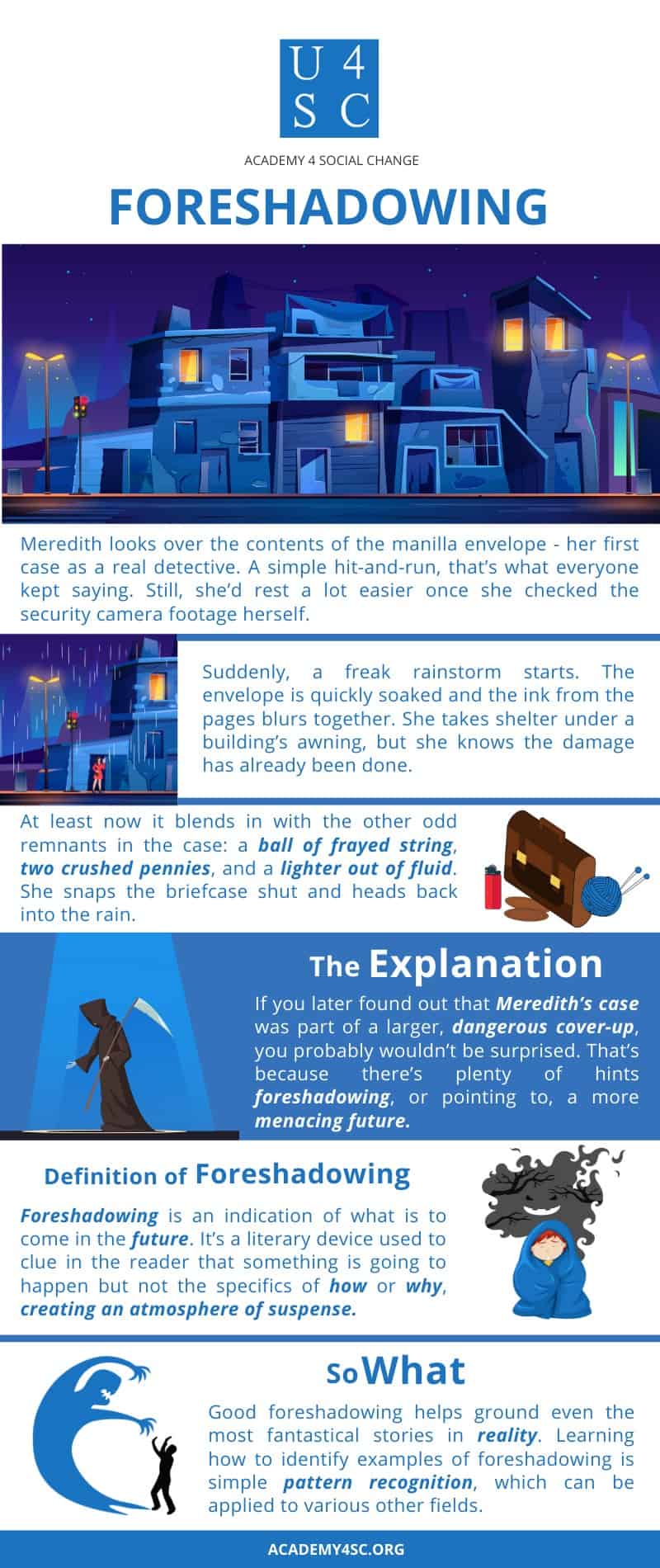

Meredith looks over the contents of the manilla envelope once more - her first case as a real detective. A simple hit-and-run, that’s what everyone kept saying. Still, she’d rest a lot easier once she checked the security camera footage herself. It would only take a minute anyways.

About halfway through her walk there, a freak rainstorm starts. The envelope is quickly soaked and the ink from the pages blurs together. Meredith takes shelter under a building’s awning to put the papers back in her briefcase, but she knows the damage had already been done. At least now it blends in with the other odd remnants in the case: a ball of frayed string, two crushed pennies, and a lighter out of fluid. “I’ll toss them after today,” she resolves, snapping the briefcase shut and heading back into the rain.

Explanation

If you later found out that Meredith’s case wasn’t so cut and dry but part of a larger, dangerous cover-up, you probably wouldn’t be surprised. That’s because there’s plenty of hints foreshadowing, or pointing to, a more menacing future, like the sudden rain or the destruction of the official case notes.

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is an indication of what is to come in the future. It’s a literary device used to clue in the reader that something is going to happen but not the specifics of how or why, creating an atmosphere of suspense. Foreshadowing can be subtle, like an innocuous statement whose true meaning isn’t revealed until later, or direct, like a prophecy of two warriors fated to duel for the fate of the universe. While it’s not always clear what exactly is being foreshadowed until the second viewing, the hints are placed beforehand so that the audience is kept in anticipation and the later reveal or twist doesn’t seem like it came out of nowhere.

The History

The word “foreshadow” was first used in the 1570s as a verb. Picture yourself in a dim room, lit only by a small candle by the door, but you’re facing away from the door. There’s a creaking in the floorboards, and you look at the wall to see this giant shadow. You don’t know what’s come through the door until you turn around, but you see the shadow first. That’s the idea behind the term, “foreshadowing” - a shadow thrown before an advancing person or object creates a suggestive image of what’s going to arrive. The noun form didn’t catch on until the 1830s. Different people claim different numbers of classic forms of foreshadowing, but the main point to keep in mind is that most of them can be broken down into two types: direct and indirect foreshadowing.

Direct foreshadowing is easy to spot. It’s the prophetic dream the hero has late at night about a coming battle. It’s the name drop of a character not yet seen who everyone seems to have strong opinions about. It’s a flashback or flash-forward that hasn’t been fully explained. Sometimes it’s even as direct as a narrator’s statement that this is the last time I’d see my good friend Jill alive. Overt foreshadowing gives more precise clues as to what’s going to happen - we know Jill is going to die, but we don’t know how or why - which makes it more noticeable on the first viewing.

Indirect foreshadowing is a little more subtle. Instead of being specifically told a detail or two, an overall uneasy atmosphere is created, setting the viewer on edge even though they don't know what’s going to go wrong. A classic example of this is change in the weather. When a movie scene suddenly includes rain, the audience knows that the heist is about to go wrong or emotional tension will be at its peak between the group, whereas the sun breaking through symbolizes an eventual turn around and happy ending. Symbolism is normally easy to spot but not always easy to decipher. The most covert examples often come in the form of innocuous statements or object introductions. If Meredith’s lighter ends up being used at a climactic moment, her briefcase inventory list serves as a hint to its later use.

Applying It

Good foreshadowing helps ground even the most fantastical stories in reality. If Meredith’s inventory wasn’t listed early on, it’d seem pretty far-fetched that she just happens to have some string to distract a cat from alerting its owner to her presence at a pivotal moment. Without foreshadowing, some plot points will feel unearned, either like the author is including random scenes in her story or letting her characters escape situations they shouldn’t. On the other hand, if you overuse foreshadowing, you’ll make what’s going to happen too obvious, killing all suspense as you hammer in the point again and again.

While foreshadowing seems strictly contained to the realm of literature and film, this isn’t actually the case. Learning how to identify examples of foreshadowing is simple pattern recognition, which can be applied to various other fields. There are hundreds of online articles claiming how certain historical events foreshadowed future ones. Reading the political atmosphere and predicting future changes is much easier if you can spot the forewarnings of how things might develop. Furthermore, learning how to tell a good story significantly improves your public speaking abilities. Whether you tell stories or simply enjoy hearing them, foreshadowing will help prepare you for future endeavors.