Introduction

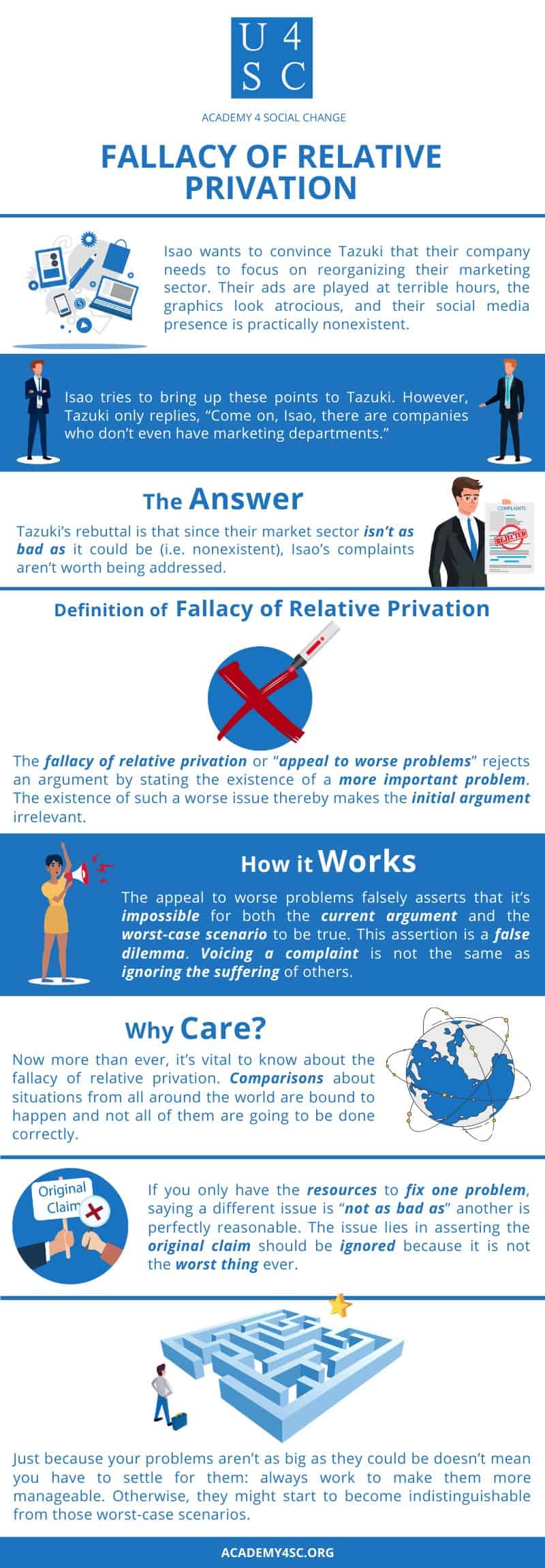

Isao wants to convince his coworker Tazuki that their company needs to focus on reorganizing their marketing sector. Their ads are played at terrible hours, the graphics of posters look atrocious, and their social media presence is practically nonexistent. Isao tries to bring up these points to Tazuki. However, Tazuki only replies, “Come on, Isao, there are companies who don’t even have marketing departments.”

Explanation

Tazuki’s rebuttal is that since their market sector isn’t as bad as it could be (i.e. nonexistent), Isao’s complaints aren’t worth being addressed.

Fallacy of Relative Privation

This is an example of a fallacy called the fallacy of relative privation. The fallacy of relative privation rejects an argument by stating the existence of a more important problem. The existence of such a worse issue, the fallacy insists, thereby makes the initial argument irrelevant. This fallacy is also known as the appeal to worse problems or “not as bad as”.

How It Works

The appeal to worse problems falsely asserts that it’s impossible for both the current argument and the worst-case scenario to be true. This assertion is a false dilemma. Voicing a complaint is not the same as ignoring the suffering of others or insisting such suffering does not exist.

For example, let’s say your friend Pip makes dinner for the two of you. After eating, he asks for your opinion. “It was lovely,” you reply, “but the chicken was a tad dry.” Pip angrily replies, “Well, there’s plenty of starving people who would love a burnt chicken, let alone a dry one!”

When Pip commits the fallacy of relative privation, he equates your criticism “the chicken was a tad dry” to a worst-case scenario of starving. Pip’s dramatic statement, while certainly true, does not negate your criticism. However, it does distract from your point and make you seem unsympathetic to any onlookers.

The fallacy of relative privation can also be presented in the “not as good as” format. For example, if Alice tells her aunt that she won second place at the science fair, the aunt is committing a fallacy if she responds, “Only second place? I guess you’re not as bright as I thought.” This variant compares the original argument to the best-case scenario rather than the worst and similarly concludes such an argument must be false since the compared scenarios are not equivalent. This variant of relative privation is not as commonly used. Thus, when someone mentions the fallacy of relative privation, they are almost always referring to the “not as bad as” variant.

So What

Now more than ever, it’s vital to know about the fallacy of relative privation. We can talk to someone on the other side of the planet and stay informed on their country’s politics. We can look up information about international incidents moments after they occur. Comparisons about situations from all around the world are bound to happen and not all of them are going to be done correctly.

In fact, you’ve likely seen a variant of this fallacy: does the phrase, “first world problem”, sound familiar? You’ll probably find it commented on a post complaining about a faulty espresso maker. Labeling something as a first world problem is the same as saying, “You’re not struggling for the basic necessities, so your problem isn’t really a problem.” Doesn’t that sound similar to the previous examples?

Not all comparisons are necessarily fallacies. If you only have the resources to fix one problem, saying a different issue is “not as bad as” another is perfectly reasonable. In fact, the comparison itself isn’t problematic. The issue lies in asserting the original claim should be ignored because it is not the worst thing ever.

Just because your problems aren’t as big as they could be doesn’t mean you have to settle for them: always work to make them more manageable. Otherwise, they might start to become indistinguishable from those worst-case scenarios.