Introduction

Sofia and her friend Gabriel decide to start a lawn-mowing business. To start, they’ve decided they will each go to a few of their neighbors, offer to mow the lawn, and see what price their neighbors offer. They figure this will help them figure out what a reasonable price is for their services. Each goes to four houses, but when they regroup, they learn that their neighbors consistently offered Sofia lower rates than Gabriel.

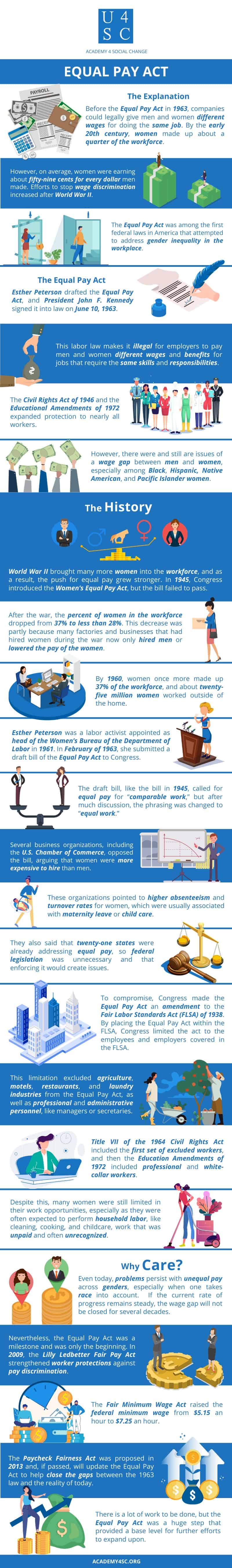

Explanation

Before the Equal Pay Act in 1963, companies could legally give men and women different wages for doing the same job. By the early 20th century, women made up about a quarter of the workforce. However, on average, women were earning about fifty-nine cents for every dollar men made. Efforts to stop wage discrimination increased after World War II when many women had stepped into jobs that men had previously held. The Equal Pay Act was among the first federal laws in America that attempted to address gender inequality in the workplace.

The Equal Pay Act

Esther Peterson drafted the Equal Pay Act, and President John F. Kennedy signed it into law on June 10, 1963. This labor law makes it illegal for employers to pay men and women different wages and benefits for jobs that require the same skills and responsibilities, and it is an amendment to the Fair Standards Act. While it was initially limited in scope, the Civil Rights Act of 1946 and the Educational Amendments of 1972 expanded protection to nearly all workers. The Equal Pay Act was an important step forward; however, there were and still are issues of a wage gap between men and women, especially among Black, Hispanic, Native American, and Pacific Islander women.

The History

World War II brought many more women into the workforce, and as a result, the push for equal pay grew stronger. In 1945, Congress introduced the Women’s Equal Pay Act, but the bill failed to pass. After the war, the percent of women in the workforce dropped from 37% to less than 28%. This decrease was partly because many factories and businesses that had hired women during the war now only hired men or lowered the pay of the women. By 1960, women once more made up 37% of the workforce, and about twenty-five million women worked outside of the home.

Esther Peterson was a labor activist appointed as head of the Women’s Bureau of the Department of Labor in 1961. In February of 1963, she submitted a draft bill of the Equal Pay Act to Congress, after working to win over opponents and gather data. The draft bill, like the bill in 1945, called for equal pay for “comparable work,” but after much discussion, the phrasing was changed to “equal work.”

Several business organizations, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, opposed the bill, arguing that women were more expensive to hire than men. These organizations pointed to higher absenteeism and turnover rates for women, which were usually associated with maternity leave or child care. They also said that twenty-one states were already addressing equal pay, so federal legislation was unnecessary and that enforcing it would create issues.

To compromise with these concerns, Congress made the Equal Pay Act an amendment to an existing law: the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938. By placing the Equal Pay Act within the FLSA, Congress limited the act to the employees and employers covered in the FLSA. This limitation excluded agriculture, motels, restaurants, and laundry industries from the Equal Pay Act, as well as professional and administrative personnel, like managers or secretaries. Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act included the first set of excluded workers, and then the Education Amendments of 1972 included professional and white-collar workers.

Though the bill was an essential step toward equality in the workforce and represents the concerted efforts of many women, the Equal Pay Act did not solve the problem of the wage gap. Many women were still limited in their work opportunities, especially as women with husbands or children were often expected to perform household labor, like cleaning, cooking, and childcare, work that was unpaid and often unrecognized.

Why Care?

Even today, problems persist with unequal pay across genders, especially when one takes race into account. In 2019, Asian American women made ninety cents for every dollar a man earned, and white women made seventy-nine cents on the dollar. Black women made sixty-two cents on the dollar, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander women made sixty-one cents. Native American and Alaskan Native women made fifty-seven cents on the dollar, and Hispanic women made fifty-four cents. If the current rate of progress remains steady, the wage gap will not be closed for several decades.

Nevertheless, the Equal Pay Act was a milestone and was only the beginning. In 2009, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act strengthened worker protections against pay discrimination. The Fair Minimum Wage Act raised the federal minimum wage from $5.15 an hour to $7.25 an hour. The Paycheck Fairness Act was proposed in 2013 and, if passed, will update the Equal Pay Act to help close the gaps between the 1963 law and the reality of today with measures such as requiring employers to prove that pay disparities exist for legitimate reasons. There is a lot of work to be done, but the Equal Pay Act was a huge step that provided a base level for further efforts to expand upon.