Introduction

It’s the second Tuesday in November: the day of the presidential election. You’ve done your research, chosen your favorite candidate, and you’re ready to go vote. When you fill out your ballot, you mark the box next to that candidate’s name. You’ve done it - you’ve voted for your candidate! Haven’t you?

The Answer

Not exactly. Even though you checked the box next to the presidential candidate’s name, you were really voting for someone whose name likely was not on the ballot at all: your elector. After the election, your elector will cast their vote for president through a process called the Electoral College.

The Electoral College

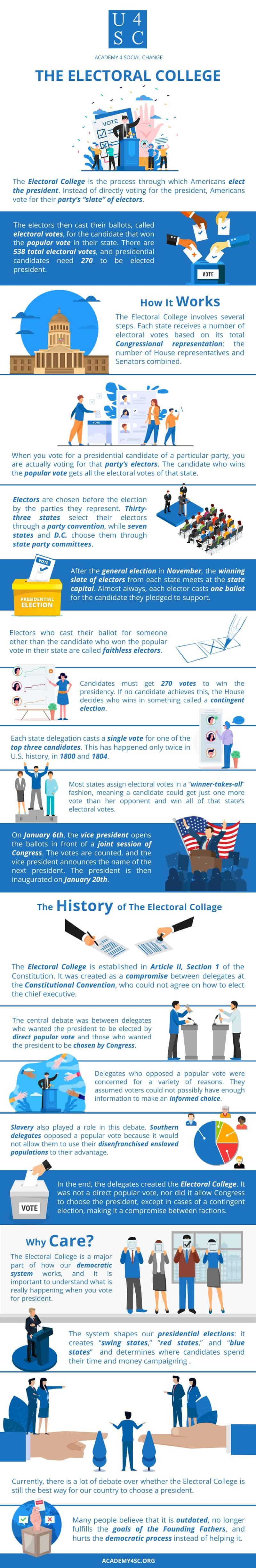

The Electoral College is the process through which Americans elect the president. Instead of directly voting for the president, Americans vote for their party’s “slate” of electors. The electors then cast their ballots, called electoral votes, for the candidate that won the popular vote in their state. There are 538 total electoral votes, and presidential candidates need 270 to be elected president.

How It Works

The Electoral College involves several steps. Each state receives a number of electoral votes based on its total Congressional representation: the number of House representatives and Senators combined. Though it is not represented in Congress, the 23rd Amendment gave the District of Columbia three electors; previously, it could not participate in presidential elections. Puerto Rico and other non-state territories do not have any electoral votes. American citizens in these places cannot participate in the general election, though they can vote in primaries.

When you vote for a presidential candidate of a particular party, you are actually voting for that party’s electors. In every state except Maine and Nebraska, the candidate who wins the popular vote gets all the electoral votes of that state. So, if the Democratic candidate wins the popular vote in New York, then the Democratic Party gets to send its slate of electors to the Electoral College. If the Republican candidate wins in New York, the Republican Party sends its slate of electors. Maine and Nebraska both have a district system. Two at-large electors represent whichever candidate won the state as a whole, and one elector represents the winner of each congressional district.

Electors are chosen before the election by the parties they represent. Thirty-three states select their electors through a party convention, while seven states and D.C. choose them through state party committees. The other ten states select electors through a combination of appointments by governors, party nominees, state chairs, presidential nominees, and other individuals. Generally, electors must be party members and registered to vote, and they must pledge to vote based on the party’s ticket - although they are not constitutionally bound to do so.

After the general election in November, the winning slate of electors from each state meets at the state capital. Almost always, each elector casts one ballot for the candidate they pledged to support. However, only 26 states and D.C. “bind” the electors to that candidate through a combination of oaths, fines, and other methods. Electors who cast their ballot for someone other than the candidate who won the popular vote in their state are called faithless electors. Though faithless electors have been present in multiple elections, they have never decided the presidency. In the modern era, electors almost always vote for the candidate to whom they are pledged, although there were seven faithless electors in the 2016 election.

Candidates must get 270 votes to win the presidency. If no candidate achieves this, the House decides who wins in something called a contingent election. Each state delegation casts a single vote for one of the top three candidates. This has happened only twice in U.S. history, in 1800 and 1804.

Most states assign electoral votes in a “winner-takes-all” fashion, meaning a candidate could get just one more vote than her opponent and win all of that state’s electoral votes. Therefore, a candidate can win the Electoral College but lose the popular vote. In fact, this has happened five times in U.S. history: with John Quincy Adams in 1824, Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, Benjamin Harrison in 1888, George W. Bush in 2000, and Donald J. Trump in 2016.

On January 6th, the vice president opens the ballots from each state in front of a joint session of Congress. The votes are counted, and the vice president announces the name of the next president. The president is then inaugurated on January 20th.

The History of the Electoral College

The Electoral College is established in Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution. It was created as a compromise between delegates at the Constitutional Convention, who could not agree on how to elect the chief executive. The central debate was between delegates who wanted the president to be elected by direct popular vote and those who wanted the president to be chosen by Congress.

Delegates who opposed a popular vote were concerned for a variety of reasons. They assumed voters could not possibly have enough information to make an informed choice. As delegate George Mason of Virginia explained at the time, “The extent of the Country renders it impossible that the people can have the requisite capacity to judge of the respective pretensions of the Candidates.” Many delegates assumed that uninformed Americans would default to voting for candidates from their home state. This was a major concern for small states. As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist 68, small states believed that under a direct popular vote, all presidents would hail from larger states.

Slavery also played a role in this debate. Southern delegates opposed a popular vote because it would not allow them to use their disenfranchised enslaved populations to their advantage. If Congress chose the president, the ⅗ Compromise would allow the South to have a more significant say. Southern states would not have this advantage under a direct popular vote.

In the end, the delegates created the Electoral College. It was not a direct popular vote, nor did it allow Congress to choose the president, except in cases of a contingent election, making it a compromise between factions.

Why Care?

The Electoral College is a major part of how our democratic system works, and it is important to understand what is really happening when you vote for president. The system shapes our presidential elections: it creates “swing states,” “red states,” and “blue states” and determines where candidates spend their time and money campaigning . Currently, there is a lot of debate over whether the Electoral College is still the best way for our country to choose a president. Much of that debate stems from the beginnings of the Electoral College and the original reasons for its establishment. Many people believe that it is outdated, no longer fulfills the goals of the Founding Fathers, and hurts the democratic process instead of helping it.