Background

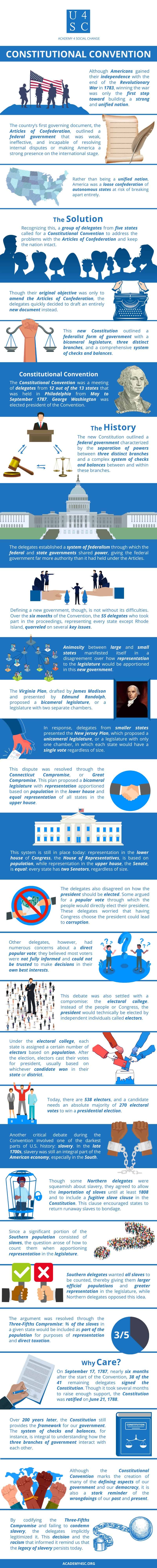

Although Americans gained their independence with the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, winning the war was only the first step toward building a strong and unified nation. The country’s first governing document, the Articles of Confederation, outlined a federal government that was weak, ineffective, and incapable of resolving internal disputes or making America a strong presence on the international stage. Rather than being a unified nation, America was a loose confederation of autonomous states at risk of breaking apart entirely.

The Solution

Recognizing this, a group of delegates from five states called for a Constitutional Convention to address the problems with the Articles of Confederation and keep the nation intact. Though their original objective was only to amend the Articles of Confederation, the delegates quickly decided to draft an entirely new document instead. This new Constitution outlined a federalist form of government with a bicameral legislature, three distinct branches, and a comprehensive system of checks and balances.

Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention was a meeting of delegates from 12 out of the 13 states that was held in Philadelphia from May to September 1787. George Washington was elected president of the Convention, and other delegates included James Madison, Ben Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton.

The History

The new Constitution outlined a federal government characterized by the separation of powers between three distinct branches and a complex system of checks and balances between and within these branches. The delegates detailed the powers of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches and constructed a system of limits and controls on each branch to ensure that none of the three could become too powerful. They established a system of federalism through which the federal and state governments shared power, giving the federal government far more authority than it had held under the Articles.

Defining a new government, though, is not without its difficulties. Over the six months of the Convention, the 55 delegates who took part in the proceedings, representing every state except Rhode Island, quarreled on several key issues.

Animosity between large and small states manifested itself in a disagreement over how representation to the legislature would be apportioned in this new government. The Virginia Plan, drafted by James Madison and presented by Edmund Randolph, proposed a bicameral legislature, or a legislature with two separate chambers. Representation in both chambers would be apportioned based on the population or wealth of each state. This plan appealed to the larger states because it would give them greater representation in the federal government. In response, delegates from smaller states presented the New Jersey Plan, which proposed a unicameral legislature, or a legislature with only one chamber, in which each state would have a single vote regardless of size.

This dispute was eventually resolved through the Connecticut Compromise, or Great Compromise. This plan proposed a bicameral legislature with representation apportioned based on population in the lower house and equal representation of all states in the upper house. This system is still in place today: representation in the lower house of Congress, the House of Representatives, is based on population, while representation in the upper house, the Senate, is equal: every state has two Senators, regardless of size.

The delegates also disagreed on how the president should be elected. Some argued for a popular vote through which the people would directly elect their president. These delegates worried that having Congress choose the president could lead to corruption between the executive and legislative branches. Other delegates, however, had numerous concerns about a direct popular vote; they believed most voters were not fully informed and could not be trusted to make decisions in their own best interests, worried that a “democratic mob” could force the country to make poor decisions, and feared the emergence of a populist president with too much power.

This debate was also settled with a compromise: the electoral college. Instead of the people or Congress, the president would technically be elected by independent individuals called electors. Under the electoral college, each state is assigned a certain number of electors based on population. After the election, electors cast their votes for president, usually based on whichever candidate won in their state or district. Today, there are 538 electors, and a candidate needs an absolute majority of 270 electoral votes to win a presidential election.

Another critical debate during the Convention involved one of the darkest parts of U.S. history: slavery. In the late 1700s, slavery was still an integral part of the American economy, especially in the South, and some southern states threatened to refuse to ratify the Constitution if their economic interests were not protected. Though some Northern delegates were squeamish about slavery, they agreed to allow the importation of slaves until at least 1808 and to include a fugitive slave clause in the Constitution. This clause encouraged states to return runaway slaves to bondage.

Since a significant portion of the Southern population consisted of slaves, the question arose of how to count them when apportioning representation in the legislature. Southern delegates wanted all slaves to be counted, thereby giving them larger official populations and greater representation in the legislature, while Northern delegates opposed this idea. The argument was resolved through the Three-Fifths Compromise: ⅗ of the slaves in a given state would be included as part of the population for purposes of representation and direct taxation.

Why Care?

On September 17, 1787, nearly six months after the start of the Convention, 38 of the 41 remaining delegates signed the Constitution. According to Article VII of the document itself, the new Constitution could not be binding until it was approved by nine of the thirteen states. Though it took several months to raise enough support, the Constitution was ratified on June 21, 1788.

Over 200 years later, the Constitution still provides the framework for our government. The system of checks and balances, for instance, is integral to understanding how the three branches of government interact with each other in the modern context. For example, the delegates established judicial review, or the power of federal courts to declare laws and presidential actions unconstitutional, a power the Supreme Court exercises today. They also established the presidential veto, which has been controversial in recent years.

Although the Constitutional Convention marks the creation of many of the defining aspects of our government and our democracy, it is also a stark reminder of the wrongdoings of our past and present. By codifying the Three-Fifths Compromise and failing to condemn slavery, the delegates implicitly legitimized it. This decision and the racism that informed it remind us that the legacy of slavery persists today; though the Three-Fifths Compromise was officially repealed by the 14th Amendment in 1868, the mistreatment of African Americans by government institutions is far from a thing of the past.