Introduction

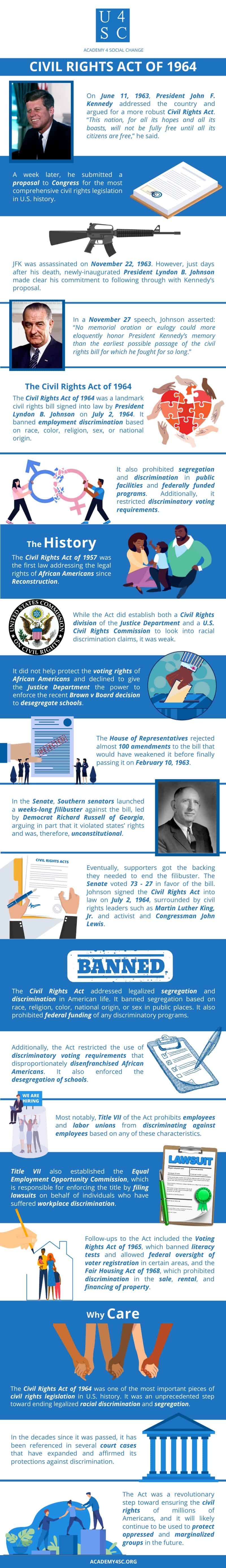

On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy addressed the country in a televised speech that argued emphatically for a more robust Civil Rights Act. “This nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free,” he said. A week later, he submitted a proposal to Congress for the most comprehensive civil rights legislation in U.S. history.

JFK was assassinated on November 22, 1963, and never saw his bill become law. However, just days after his death, newly-inaugurated President Lyndon B. Johnson made clear his commitment to following through with Kennedy’s proposal. In a November 27 address to a joint session of Congress, Johnson asserted: “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought for so long.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark civil rights bill signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 2, 1964. It banned employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It also prohibited segregation and discrimination based on those characteristics in public facilities and federally funded programs. Additionally, it restricted discriminatory voting requirements.

The History

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first law addressing the legal rights of African Americans since Reconstruction. While the Act did establish both a Civil Rights division of the Justice Department and a U.S. Civil Rights Commission to look into racial discrimination claims, it was weak. The Act did little to lessen rampant discrimination and segregation in the country. It did not help protect the voting rights of African Americans and declined to give the Justice Department the power to enforce the recent Brown v Board decision to desegregate schools.

By 1963, rapidly growing frustration about the racism entrenched in American life led Kennedy to propose and fight for a new civil rights act. When he was assassinated in November 1963, Johnson continued the campaign. “Let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined,” he declared in his first State of the Union address. Getting the Act passed, however, was no easy feat.

The House of Representatives rejected almost 100 amendments to the bill that would have weakened it before finally passing it on February 10, 1963. In the Senate, Southern senators launched a weeks-long filibuster against the bill, arguing in part that it violated states’ rights and was, therefore, unconstitutional. The filibuster was led by Democrat Richard Russell of Georgia, who asserted, “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which could have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our [Southern] states.”

Eventually, though, supporters got the backing they needed to end the filibuster. The Senate voted 73 - 27 in favor of the bill. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964, surrounded by civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and activist and Congressman John Lewis.

The Civil Rights Act addressed legalized segregation and discrimination in American life. It banned segregation based on race, religion, color, national origin, or sex in public places. It also prohibited federal funding of any discriminatory programs. Additionally, the Act restricted the use of discriminatory voting requirements that disproportionately disenfranchised African Americans, such as literacy tests. It also enforced the desegregation of schools.

Most notably, Title VII of the Act prohibits employees and labor unions from discriminating against employees based on any of these characteristics. Employees could no longer be denied employment or be treated any differently in the workplace because of their race, religion, color, national origin, or sex. Title VII also established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which is responsible for enforcing the title by filing lawsuits on behalf of individuals who have suffered workplace discrimination.

Follow-ups to the Act included the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which banned literacy tests entirely and allowed federal oversight of voter registration in certain areas, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of property.

Why Care?

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was one of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history. It was an unprecedented step toward ending legalized racial discrimination and segregation. In the decades since it was passed, it has been referenced in several court cases that have expanded and affirmed its protections against discrimination. In the 1971 case Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., for instance, the Supreme Court ruled that based on the Act, companies cannot discriminate against female job applicants because they have a preschool-aged child unless they have the same policy for male applicants.

In June 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County that discrimination on the basis of sex includes discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Therefore, Title VII protections against workplace discrimination apply to LGBTQ+ individuals. Prior to the decision, it was legal to fire workers because of their sexuality or gender identity in over half of the states. The Act was a revolutionary step toward ensuring the civil rights of millions of Americans, and it will likely continue to be used to protect oppressed and marginalized groups in the future.