Introduction

It is the evening of March 7, 1965. You and your family, along with 50 million other Americans, are watching the highly-anticipated television premiere of “Judgment at Nuremberg,” a film that explores the decisions of Nazis who followed orders instead of speaking out against the Holocaust. All of a sudden, the movie is interrupted. Instead of the film, you see White state troopers beating unarmed Black men and women. Where is this? What is happening?

Explanation

The footage you are seeing was taken earlier that day in Selma, Alabama, where state troopers and law enforcement officers beat and tear-gassed activists peacefully protesting for their right to vote. The violent event becomes known as Bloody Sunday.

Bloody Sunday

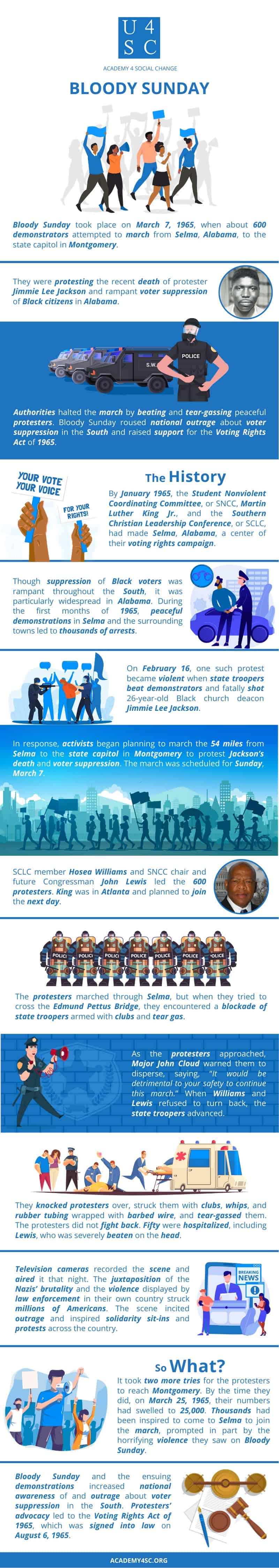

Bloody Sunday took place on March 7, 1965, when about 600 demonstrators attempted to march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capitol in Montgomery. They were protesting the recent death of protester Jimmie Lee Jackson and rampant voter suppression of Black citizens in Alabama. Authorities halted the march by beating and tear-gassing peaceful protesters. Bloody Sunday roused national outrage about voter suppression in the South and raised support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The History

By January 1965, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC, had made Selma, Alabama, a center of their voting rights campaign. Though suppression of Black voters was rampant throughout the South, it was particularly widespread in Alabama. During the first months of 1965, peaceful demonstrations in Selma and the surrounding towns led to thousands of arrests. On February 16, one such protest became violent when state troopers beat demonstrators and fatally shot 26-year-old Black church deacon Jimmie Lee Jackson.

In response, activists began planning to march the 54 miles from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery to protest Jackson’s death and voter suppression. The march was scheduled for Sunday, March 7. SCLC member Hosea Williams and SNCC chair and future Congressman John Lewis led the 600 protesters. King was in Atlanta and planned to join the next day.

The protesters marched through Selma, but when they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they encountered a blockade of state troopers armed with clubs and tear gas. As the protesters approached, Major John Cloud warned them to disperse, saying, “It would be detrimental to your safety to continue this march.” When Williams and Lewis refused to turn back, the state troopers advanced. They knocked protesters over, struck them with clubs, whips, and rubber tubing wrapped with barbed wire, and tear-gassed them. The protesters did not fight back. Fifty were hospitalized, including Lewis, who was severely beaten on the head.

Television cameras recorded the scene, and footage of the violence aired that night. The juxtaposition of the Nazis’ brutality and the violence displayed by law enforcement in their own country struck millions of Americans. The scene incited outrage and inspired solidarity sit-ins and protests across the country.

So What?

It took two more tries for the protesters to reach Montgomery. By the time they did so, on March 25, 1965, their numbers had swelled to 25,000. Thousands had been inspired to come to Selma to join the march, prompted in part by the horrifying violence they saw on Bloody Sunday. Bloody Sunday and the ensuing demonstrations increased national awareness of and outrage about voter suppression in the South. Protesters’ advocacy led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was signed into law on August 6, 1965.