Introduction

Your family does household chores weekly, with each person’s responsibilities rotating with the week. Your sister recently admitted that she greatly prefers taking care of the trash and recycling while your brother’s favorite chores are doing the dishes and vacuuming. With this new information in mind, you propose a new chore system to your family. Instead of switching jobs each week, why not keep them fixed? Since everyone has a different opinion on which chore is the best or worst to do, each person could get permanently assigned to their preferred chore and never have to do their most hated one ever again.

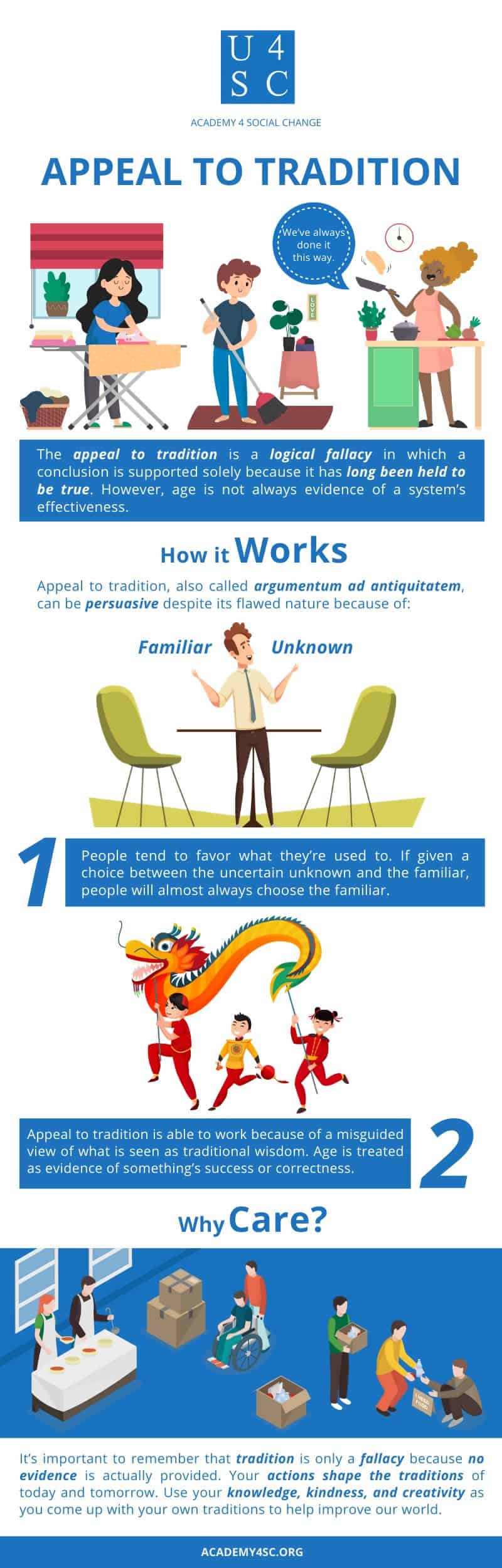

Your parents are not impressed with your idea. They dismiss the proposed system, saying, “We’ve always done chores this way.”

Explanation

When your parents argue against your new chore system, they’re making an appeal to tradition. They cite the current chore system’s long use without providing any actual evidence as to why it’s the superior system.

Appeal to Tradition

The appeal to tradition is a logical fallacy in which a conclusion or side is supported solely because it has long been held to be true or superior. However, age is not always evidence of a system’s truth or effectiveness.

How It Works

Appeal to tradition, also called argumentum ad antiquitatem, can be persuasive despite its flawed nature for a number of reasons.

First off, people tend to favor what they’re used to. If given a choice between the uncertain unknown and the familiar, people will almost always choose the familiar. Part of this may be because of laziness. It takes much less effort to stay with the norm than to try out something new. People might also stick with the familiar out of fear. The unknown can be frightening while the familiar, even if it has problems, is generally viewed as safer.

Furthermore, appeal to tradition is able to work because of a misguided view of what is seen as traditional wisdom. Age is treated as evidence of something’s success or correctness. If a system lasted for this long, it must be effective. If a belief prevailed to this day, it must be true. However, age isn’t necessarily indicative of any of these attributes. Plenty of morally wrong beliefs, like racism and sexism, have a lengthy history. In addition, a lot of incorrect medical procedures were routinely done for centuries even though they routinely decreased a patient’s health. It was also widely held that the sun revolved around the earth for a long time even though that wasn’t the case. Just because something has become a “tradition” doesn’t mean it deserves to.

So What

People make appeals to tradition in all kinds of arguments. It’s important to remember that this is only a fallacy because no evidence is actually provided. If someone mentions that a custom is “tradition” but provides supporting facts and/or figures on why this tradition is helpful or important, then that’s a legitimate argument. Basing an argument on an appeal to tradition instead of concrete evidence is committing a logical fallacy.

Traditions only come about because one person decides to act and think differently. Your actions shape the traditions of today and tomorrow. Use your knowledge, kindness, and creativity as you come up with your own traditions to help improve our world.