Introduction

Think of the last time you were rejected for something—a scholarship, an internship, or a spot on a sports team. How did you explain it to yourself? Did you blame it on unfairness, make judgments about the person who was chosen, or identify a weakness in your own qualifications? As human beings, we have this burning desire to know why, especially when making sense of things that affect our own lives and understanding of the world. But we don’t always consider all the possible explanations for a given result or observation. In this lesson, you’ll learn how investigating alternative explanations is something we all can and should do, because it helps us get closer to the truth of the matter and to be more persuasive advocates for the causes that matter to us.

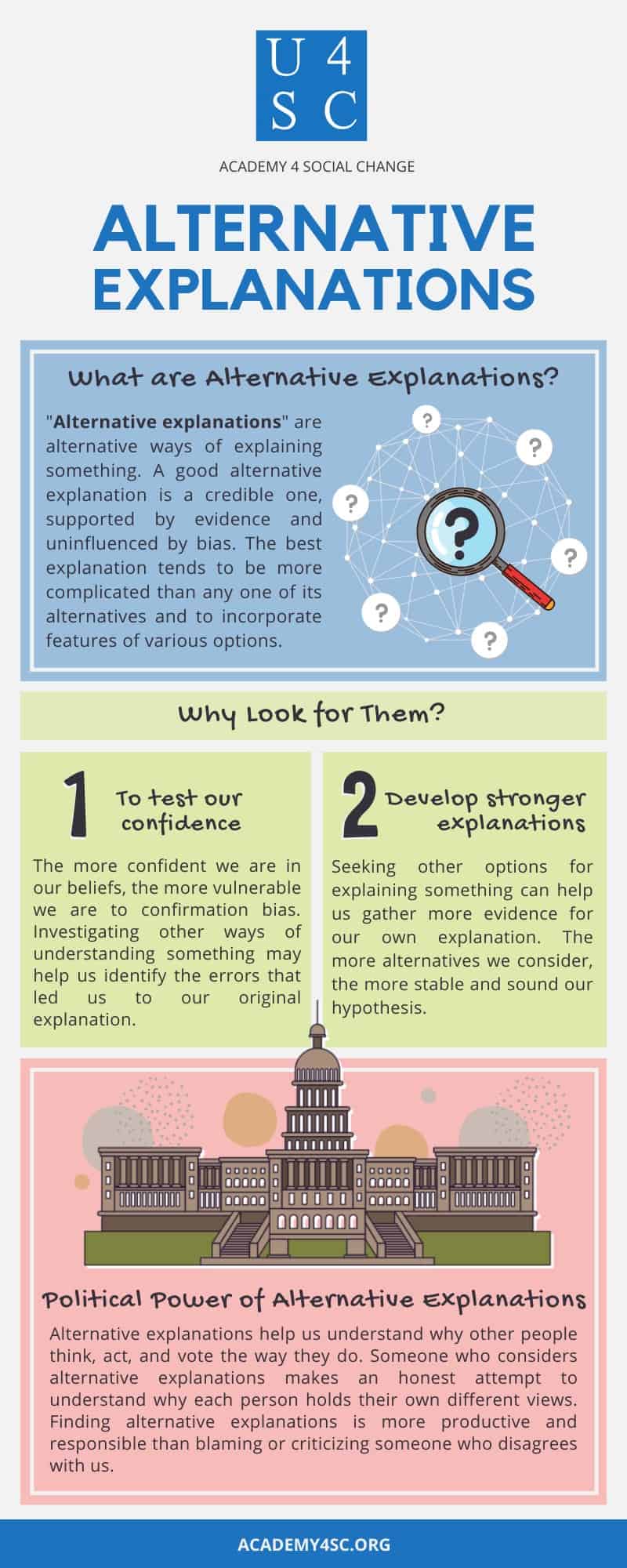

What Are Alternative Explanations?

As the name suggests, alternative explanations are alternative ways of explaining something. A good alternative explanation is a credible one, supported by evidence and uninfluenced by bias. Consider climate change today. Various explanations can and have been used to explain the sharp increase in global temperatures, especially since the mid-1900s. Both human activity and changes in how much solar energy reaches the sun have been proposed as explanations for this phenomenon. To identify the best explanation, we should weigh the evidence, in this case scientific evidence, for each one and account for biases (e.g., political and economic motives) that may motivate defenders of each one. The best explanation tends to be more complicated than any one of its alternatives and to incorporate features of various options.

Why Look for Them?

Discovering the true explanation for anything is extremely difficult, as you’ve probably learned in your history or science classes. But working toward the best explanation is within our reach, and we are more likely to find the best explanation when we consider plausible alternative explanations. There are 2 key reasons to look for alternative explanations.

- To test our confidence. We tend not to consider alternatives when we think we have the best explanation, but this may be when we most need them. The more confident we are in our beliefs, the less willing we are to change our minds about them and the more vulnerable we are to confirmation bias. But this can be dangerous when the beliefs we have are based on biases, bad evidence, or ulterior movies—even if we don’t realize it. Investigating other ways of understanding something may help us identify the errors that led us to our original explanation. We may find, for example, that most other explanations do not include the evidence that was crucial to our own explanation, leading us to wonder whether this evidence really is good evidence if we are the only ones using it.

- To develop stronger explanations. Of course, we should also consider alternative explanations when our existing explanation is shaky. In these cases, seeking other options for explaining something can help us gather more evidence for our own explanation, use the process of elimination to get to a better explanation, or combine strong features of different explanations to develop a fuller picture of the right explanation. The more alternatives we consider, the more stable and sound our hypothesis.

An Example from Philosophy

Philosophers are one group that has been in the business of reasoning through alternative explanations to find the best one. Consider a recent example: moral philosopher Thomas Scanlon’s work “The Diversity of Objections to Inequality” (1997). Scanlon begins his article by reflecting on how he believes that equality is an important political goal but how, as he thinks more about it, he realizes that most of his reasons for favoring equality are actually based on values other than equality itself. He considers four explanations for his—and others’—preference for eliminating inequalities: (1) it would relieve suffering, (2) it would cancel out differences between people that lead some people to be stigmatized, (3) it would prevent some people from being dominated by others, and (4) it would ensure that certain conditions under which procedures (such as voting) take place are fair. His reflection on alternative explanations for his (and others’) attitude toward inequality leads him to reject a simple picture of this attitude. He finds that there is a diversity of reasons for his belief and realizes that, surprisingly, most don’t have to do with equality itself but its effects. This investigation puts him in a better position to advocate for equality. He has more evidence to explain his (and others’) support for equality and can defend it to people who care about each of these four effects but not equality for its own sake. So, for example, he may emphasize explanation (1) to people who care about eliminating global poverty but play up reason (4) to people who care about guarding democratic processes from the influence of wealth.

The Political Power of Alternative Explanations

As the Scanlon example shows, alternative explanations can play a powerful role in social and political movements. They help us understand why other people think, act, and vote the way they do. Someone who considers alternative explanations does not jump to the conclusion that someone who disagrees with her about a particular issue is irrational, immoral, or just plain wrong. She makes an honest attempt to understand why this person holds different views. This helps her develop a fuller picture of the person’s motivations, which can help her better target her arguments to change the person’s mindset. Finding alternative explanations is more productive and responsible than blaming or criticizing someone who disagrees with us.