Background

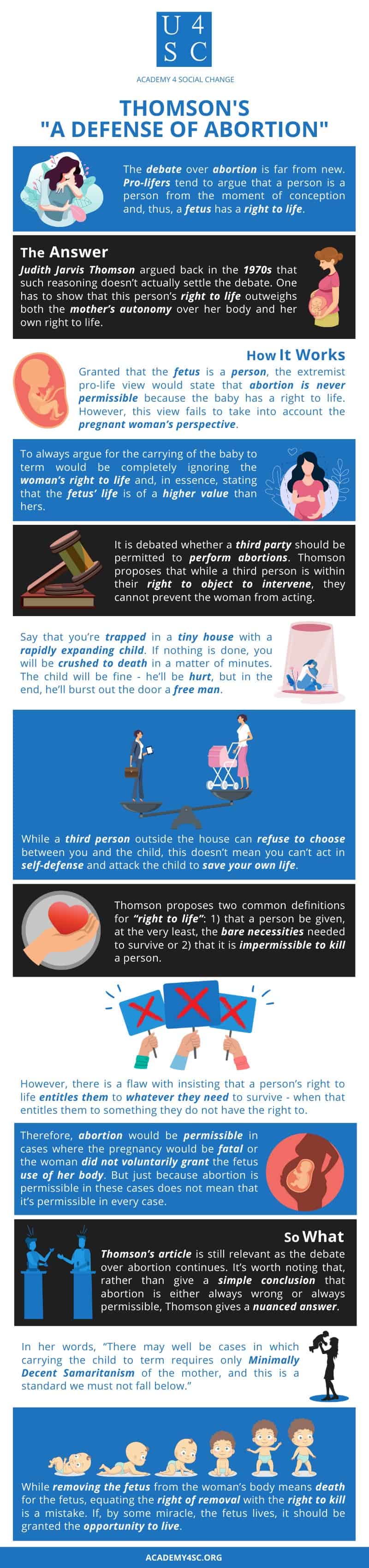

The debate over abortion, whether you’re speaking from a legal, religious, or moral perspective, is far from new. A large chunk of the arguments centers around whether the fetus is considered a person and what rights that person has in comparison to the rights of the woman carrying the child. Pro-lifers tend to argue that a person is a person from the moment of conception and, thus, a fetus has a right to life.

The Answer

Judith Jarvis Thomson argued back in the 1970s that such reasoning doesn’t actually settle the debate. Even if it’s assumed for the sake of argument that a fetus is a person from the moment of conception, nothing is proved on whether or not abortion is permissible. Rather, one would have to show that this person’s right to life outweighs both the mother’s autonomy over her body and her own right to life. Thomson attempts to see if it does in her article, “A Defense of Abortion.”

How It Works

Granted that the fetus is a person, the extremist pro-life view would state that abortion is thus never permissible because the baby has a right to life. However, this view fails to take into account the pregnant woman’s perspective. In the case where pregnancy directly threatens the mother’s life, must we insist that she has to passively wait for death? Thomson argues that most people would say no. Furthermore, to always argue for the carrying of the baby to term would be completely ignoring the woman’s right to life and, in essence, stating that the fetus’ life is of a higher value than hers.

The argument over abortion, according to Thomson, routinely ignores the woman’s perspective. Instead, it is debated whether a third party should be permitted to perform abortions. Thomson proposes that while a third person is within their right to object to intervene, they cannot prevent the woman from acting.

Thomson explains this via the “expanding child.” Say that you’re trapped in a tiny house with a rapidly expanding child. If nothing is done, you will be crushed to death in a matter of minutes. The child, on the other hand, will be fine - he’ll be hurt, but in the end, he’ll burst out the door a free man. While a third person outside the house can refuse to choose between you and the child (both innocent parties), this doesn’t mean you can’t act in self-defense and attack the child to save your own life. This hypothetical isn’t much different from fatal pregnancies, Thomson argues. To prevent a woman from getting a life-saving abortion would be to insist she wait passively for death within her own home.

The right to life allegedly prohibits abortion, yet the term is never defined. Thomson proposes two common definitions for “right to life”: 1) that a person be given, at the very least, the bare necessities needed to survive or 2) that it is impermissible to kill a person. However, both these functional meanings break down upon closer inspection.

It’s easy to find holes in the second definition - most would amend the statement by clarifying that one should not unjustly kill another. However, there is also a flaw with insisting that a person’s right to life entitles them to whatever they need to survive, namely when that entitles them to something they do not have the right to. For example, let’s say that I am terminally ill, and the only thing that can save me from death is the touch of President Barack Obama’s hand upon my brow. While it would be nice of him to do so, no one would argue that I have a right to have President Obama flown to my hospital room to bestow upon me his healing touch. Likewise, Thomson argues, no one can have a right to someone else’s body unless they are freely given that right by said individual.

Therefore, abortion would be permissible in cases where the pregnancy would be fatal or the woman did not voluntarily grant the fetus the use of her body. However, just because abortion is permissible in these cases does not mean that it’s permissible in every case.

So What?

Thomson’s article is still relevant as the debate over abortion continues. Her paper is remembered and cited today because of her vivid and succinct comparisons and hypotheticals used to make her points. Furthermore, she brought attention to a previously ignored logical gap.

Abortion is discussed not only morally but legally as well. As Thomson points out, excluding actively harming another, the United States has no law insisting that people be minimally decent to each other. For example, thirty-eight people witnessed Kitty Genovese’s murder, yet they did nothing, not even call the police, and they faced no legal punishment for their inaction. Yet criminalizing abortion forces women to not only be minimally decent but Good Samaritans. Thomson brings up this point to show the disconnect and “gross injustice” she sees in current law.

It’s worth noting that, rather than give a simple conclusion that abortion is either always wrong or always permissible, she gives a nuanced answer. In her words, “There may well be cases in which carrying the child to term requires only Minimally Decent Samaritanism of the mother, and this is a standard we must not fall below.” Furthermore, while abortion can be permissible, Thomson does not argue that the mother has a right to kill the unborn child. While removing the fetus from the woman’s body means death for the fetus, equating the right of removal with the right to kill is a mistake. If, by some miracle, the fetus lives or if it ever becomes possible to remove fetuses alive from pregnant women via scientific advancement, it should be granted the opportunity to live.