Introduction

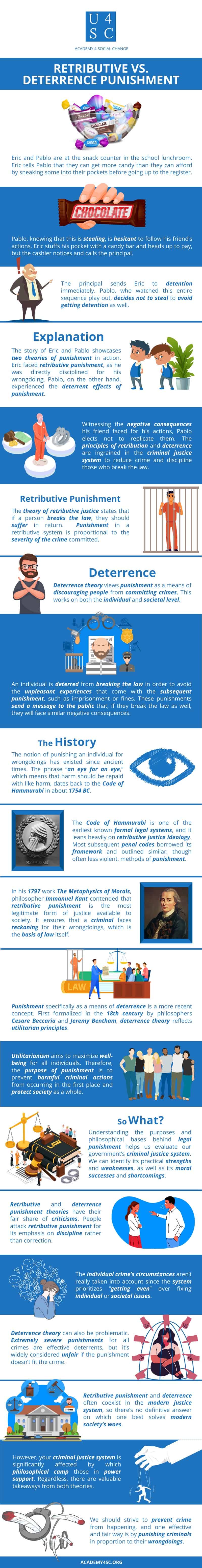

Eric and Pablo are at the snack counter in the school lunchroom. Eric tells Pablo that they can get more candy than they can afford by sneaking some into their pockets before going up to the register. Pablo, knowing that this is stealing, is hesitant to follow his friend’s actions. Eric stuffs his pocket with a candy bar and heads up to pay, but the cashier notices and calls the principal. The principal sends Eric to detention immediately. Pablo, who watched this entire sequence play out, decides not to steal to avoid getting detention as well.

Explanation

The story of Eric and Pablo showcases two theories of punishment in action. Eric faced retributive punishment, as he was directly disciplined for his wrongdoing. Pablo, on the other hand, experienced the deterrent effects of punishment. Witnessing the negative consequences his friend faced for his actions, Pablo elects not to replicate them. The principles of retribution and deterrence are ingrained in the criminal justice system to reduce crime and discipline those who break the law.

Retributive Punishment

The theory of retributive justice states that if a person breaks the law, they should suffer in return. In other words, if someone harms another person or society, the person who inflicted that wrong should endure harm of their own. Punishment in a retributive system is proportional to the severity of the crime committed.

Deterrence

Deterrence theory views punishment as a means of discouraging people from committing crimes. This works on both the individual and societal level. An individual is deterred from breaking the law in order to avoid the unpleasant experiences that come with the subsequent punishment, such as imprisonment or fines. These punishments send a message to the public that, if they break the law as well, they will face similar negative consequences.

The History

The notion of punishing an individual for wrongdoings has existed since ancient times. The phrase “an eye for an eye,” which means that harm should be repaid with like harm, dates back to the Code of Hammurabi in about 1754 BC. The Code of Hammurabi is one of the earliest known formal legal systems, and it leans heavily on retributive justice ideology. Most subsequent penal codes borrowed its framework and outlined similar, though often less violent, methods of punishment. In his 1797 work The Metaphysics of Morals, philosopher Immanuel Kant contended that retributive punishment is the most legitimate form of justice available to society. It ensures that a criminal faces reckoning for their wrongdoings, which is the basis of law itself. Retributive punishment remains a cornerstone of many modern legal systems.

Punishment specifically as a means of deterrence is a more recent concept. First formalized in the 18th century by philosophers Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, deterrence theory reflects utilitarian principles. Utilitarianism aims to maximize well-being for all individuals. As such, Beccaria and Bentham framed crime as a societal matter, not just an issue between the criminal and the victim. Therefore, the purpose of punishment is to prevent harmful criminal actions from occurring in the first place and protect society as a whole.

So What?

Understanding the purposes and philosophical bases behind legal punishment helps us evaluate our government’s criminal justice system. We can identify its practical strengths and weaknesses, as well as its moral successes and shortcomings. Good reform sprouts from a sound knowledge of the issue. For example, some countries in Europe have adopted traffic laws that dole out fines proportional to the offender’s income. In the United States, high- and low-income traffic offenders pay the same or very similar fines for identical transgressions. In Finland, though, a speeding ticket may cost upwards of €50,000 for someone who earns a multimillion-dollar salary, but only €200 for someone who earns average wages. These are all examples of retributive punishment for violating speeding laws, but Finland’s model also serves as a deterrence. A base rate fine acts as a deterrent for those with less money, but likely doesn't for wealthy offenders. They may continue to speed and pay the fine since it does not significantly hurt them financially.

Retributive and deterrence punishment theories have their fair share of criticisms. People attack retributive punishment for its emphasis on discipline rather than correction. The individual crime’s circumstances aren’t really taken into account since the system prioritizes “getting even” over fixing individual or societal issues. For example, schizophrenia patients are sometimes held in custody for disturbing the peace with the erratic behavior caused by their mental illness. This only exacerbates their condition, and thus increases their likelihood of becoming a repeat offender. Connecting them with psychiatric resources would better address their improper behaviors, lowering the likelihood of future offenses. Deterrence theory can also be problematic. Extremely severe punishments for all crimes are effective deterrents, but it’s widely considered unfair if the punishment doesn’t fit the crime. If Eric faced a $5,000 fine for stealing candy, he wouldn’t do it again. But since the candy is only worth three dollars, it’s disproportionately harsh and unjust.

Retributive punishment and deterrence often coexist in the modern justice system, so there’s no definitive answer on which one best solves modern society’s woes. However, your criminal justice system is significantly affected by which philosophical camp those in power support. Regardless, there are valuable takeaways from both theories. We should strive to prevent crime from happening, and one effective and fair way is by punishing criminals in proportion to their wrongdoings.