Background

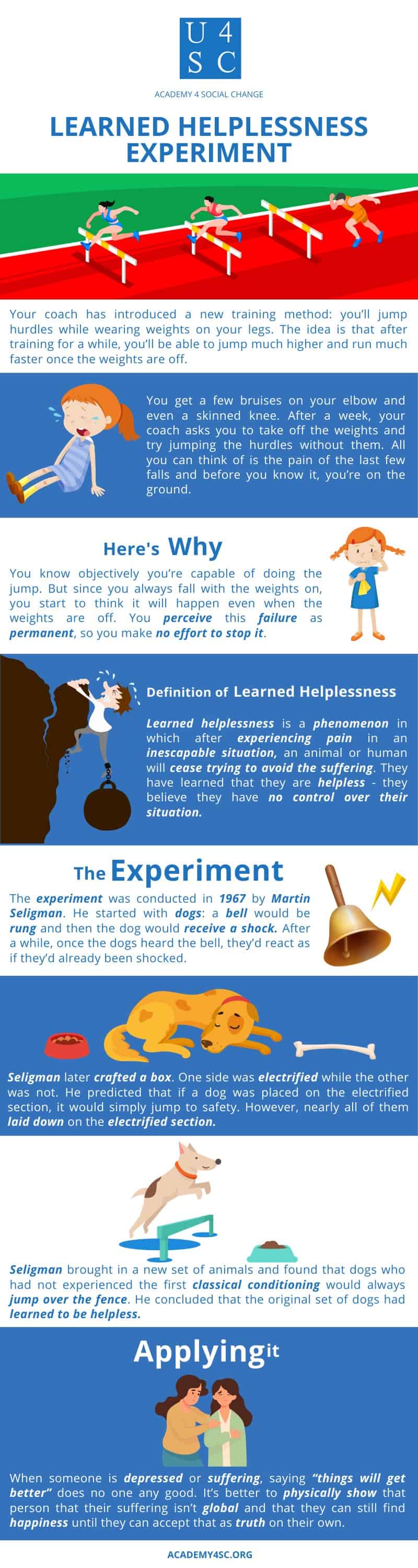

Your coach has introduced a new training method: at practice, you’ll jump hurdles while wearing weights on your legs. The idea is that after training for a while, you’ll be able to jump much higher and run much faster once the weights are off. You’re not so sure it will actually work though. Running is hard but not impossible. Jumping, however, earns you a tangled mess of limbs every time. You try different techniques, but it makes no difference. You get a few bruises on your elbow and even a skinned knee. After a week, your coach asks you to take off the weights and try jumping the hurdles without them. You get in position at the starting line and sprint to the hurdle. All you can think of is the pain of the last few falls and before you know it, you’re on the ground. Your coach is confused. “You jumped right into the hurdle - you didn’t even try to clear it.”

Here’s Why

Somewhere in the back of your mind, you know objectively you’re capable of doing the jump. But the weight training has conditioned you to think that you can’t. Since you always fall and injure yourself with the weights on, you start to think it will always happen even when the weights are off. You perceive this suffering and failure as permanent, so you make no effort to stop it from happening.

Learned Helplessness

Learned helplessness is a phenomenon in which after experiencing pain or discomfort in an inescapable situation, an animal or human will cease trying to avoid the suffering. They have learned that they are helpless - they believe they have no control over their situation, even if there is an opportunity to escape. This kind of conditioning was famously studied in Seligman’s Learned Helplessness Experiment.

The Experiment

The notable part of the experiment was conducted in 1967 at the University of Pennsylvania by Martin Seligman and his colleagues. However, it only came about because two years prior, the researchers had been experimenting with classical conditioning, which is the process by which an animal or human comes to associate one stimulus with another. Seligman experimented with dogs: first a bell would be rung and then the dog would receive a shock. After a number of pairings, the dogs were classically conditioned - once they heard the bell, they’d react as if they’d already been shocked.

Seligman later crafted a box with a low fence dividing its middle. One side was electrified while the other was not. The dog could easily see and jump over the fence. Seligman predicted that if a dog was placed on the electrified section, it would simply jump to safety. However, when he used the dogs from the earlier experiment as test subjects, nearly all of them did not move. They laid down on the electrified section they were placed on.

Seligman brought in a new set of animals and found that dogs who had not experienced the first classical conditioning would always jump over the fence. He concluded that the original set of dogs had learned to be helpless - they had no control in the first half of the experiment, so they assumed they would never have control. They believed there was nothing they could do to avoid the shocks, even when there was a clear option they could take to do so. Seligman called this condition “learned helplessness.”

Applying It

Learned helplessness has been observed in humans and animals. If bad things constantly happen outside of your control, you’re liable to start thinking you can never prevent them from happening. This is the case with victims of abuse, from physical to verbal to emotional. Even when escape seems possible, many won’t leave an abusive relationship or home because they think it won’t do them any good - they’ll get caught and end up right back where they started. It’s also been discussed that learned helplessness likely plays a strong role in depression and other mental illnesses. If you think you’re not in control, you believe your actions will make no difference. Just like one of Seligman’s classically conditioned dogs, you’ll lie down and give up.

But not every one of those dogs did lie down. Some still jumped the fence despite being test subjects in the first half of the experiment. Seligman later theorized that whether someone experiences learned helplessness has to do with the strength and type of their explanatory style. A pessimistic explanatory style involves personal blame for bad outcomes and beliefs that such suffering is permanent and pervasive. Meanwhile, an optimistic one involves external blame for negative events and beliefs that such suffering is temporary and local. For example, someone with an optimistic explanatory style might say, “I didn’t make the team because I didn’t practice hard enough.” The negative event is attributed to a lack of effort, something that can easily be remedied. Meanwhile, someone with a pessimistic explanatory in the same situation might say, “I didn’t make the team because I’m not good enough.” The suffering is internalized - the person believes they are inherently lackluster and can never remedy the situation.

These outlooks play an important role. They serve almost as self-fulfilling prophecies. If you’re optimistic and perceive your situation as malleable, you will take every opportunity to change it for the better and will likely do so because you don’t give up. If you’re pessimistic and perceive your situation as fixed, you won’t bother to try to affect it and thus stay stuck in bad situations. Your outlook affects your end goals.

Finally, it should be noted that Seligman and his colleagues did eventually get the conditioned dogs to jump over the fence. They tried many methods, but the only one that worked was picking up the dogs and moving their legs, replicating the actions the dogs themselves would need to perform to escape the electrified side. They needed to do this at least twice, i.e. create a pattern of realistic escape, before the dog would jump on its own. When someone is depressed or suffering, saying “things will get better” does no one any good. Rather, it’s better to physically show that friend that their suffering isn’t global and that they can still find happiness multiple times until they can accept that as truth on their own.