Introduction

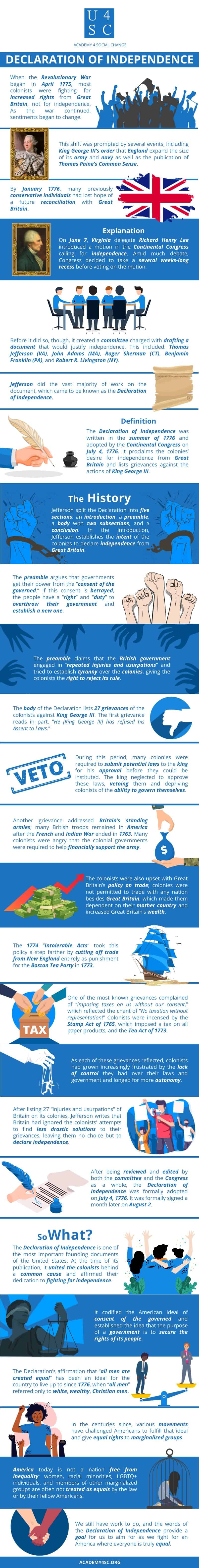

When the Revolutionary War began in April 1775, most colonists were fighting for increased rights from Great Britain, not for independence. As the war continued, however, sentiments began to change. This shift was prompted by several events, including King George III’s order that England expand the size of its army and navy as well as the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which argued that colonists had a “natural right” to independence. By January 1776, many previously conservative individuals had lost hope of a future reconciliation with Great Britain.

Explanation

On June 7, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion in the Continental Congress calling for independence. Amid much debate, Congress decided to take a several weeks-long recess before voting on the motion. Before it did so, though, it created a committee charged with drafting a document that would justify independence. This committee included five men: Thomas Jefferson (VA), John Adams (MA), Roger Sherman (CT), Benjamin Franklin (PA), and Robert R. Livingston (NY). Jefferson did the vast majority of work on the document, which came to be known as the Declaration of Independence.

Definition

The Declaration of Independence was written by Thomas Jefferson in the summer of 1776 and formally adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. It proclaims the colonies’ desire for independence from Great Britain and lists several grievances against the actions of King George III.

The History

Jefferson split the Declaration into five sections: an introduction, a preamble, a body with two subsections, and a conclusion. In the introduction, Jefferson establishes the intent of the colonies to declare independence from Great Britain, arguing that such an action is “necessary.” The preamble contains the most famous words of the document: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” The preamble argues that governments get their power from the “consent of the governed,” meaning the support of the people. If this consent is betrayed, the people have a “right” and “duty” to overthrow their government and establish a new one that will prioritize their happiness and safety. The preamble claims that the British government engaged in “repeated injuries and usurpations” and tried to establish tyranny over the colonies, giving the colonists the right to reject its rule.

The body of the Declaration lists 27 grievances of the colonists against King George III. The first grievance reads in part, “He [King George III] has refused his Assent to Laws.” During this period, many colonies were required to submit potential laws to the king for his approval before they could be instituted. The king regularly neglected to approve these laws, effectively vetoing them and depriving colonists of the ability to govern themselves. Another grievance addressed Britain’s standing armies; contrary to most colonists’ expectations, many British troops remained in America after the French and Indian War ended in 1763. Many colonists were angry that the colonial governments were required to help financially support the army and saw its presence as a threat to the popular will.

The colonists were also upset with Great Britain’s policy on trade; colonies were not permitted to trade with any nation besides Great Britain, which simultaneously made them dependent on their mother country and increased Great Britain’s wealth. The 1774 “Intolerable Acts” took this policy a step farther by cutting off trade from New England entirely as punishment for the Boston Tea Party in 1773. One of the most well-known grievances complained of “imposing taxes on us without our consent,” which reflected the famous chant of “No taxation without representation!” Colonists were particularly incensed by the Stamp Act of 1765, which imposed a tax on virtually all paper products, and the Tea Act of 1773, which imposed new taxes on tea and led to the Boston Tea Party. As each of these grievances reflected, colonists had grown increasingly frustrated by the lack of control they had over their laws and government and longed for more autonomy.

After listing 27 “injuries and usurpations” of Britain on its colonies, Jefferson writes that Britain had ignored the colonists’ attempts to find less drastic solutions to their grievances, leaving them no choice but to declare independence. He concludes by stating on behalf of the “good People of these Colonies” that the colonies are “Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved.”

After being reviewed and edited by both the committee and the Congress as a whole, the Declaration of Independence was formally adopted on July 4, 1776. It was formally signed a month later on August 2.

So What?

The Declaration of Independence is one of the most important founding documents of the United States. At the time of its publication, it united the colonists behind a common cause and affirmed their dedication to fighting for independence. It codified the American ideal of consent of the governed and established the idea that the purpose of a government is to secure the rights of its people. The Declaration’s affirmation that “all men are created equal” has been an ideal for the country to live up to since 1776, when “all men” referred only to white, wealthy, Christian men. In the centuries since, various movements have challenged Americans to fulfill that ideal and give equal rights to marginalized groups. For instance, in 1848, early women’s rights activists modeled their “Declaration of Sentiments” after the Declaration of Independence, writing, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal.” The Declaration was also referenced often during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Many activists based their appeals for racial equality in the document’s assertion that “all men are created equal.”

America today is not a nation free from inequality: women, racial minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and members of other marginalized groups are often not treated as equals by the law or by their fellow Americans. We still have work to do, and the words of the Declaration of Independence provide a goal for us to aim for as we fight for an America where everyone is truly equal.