Introduction

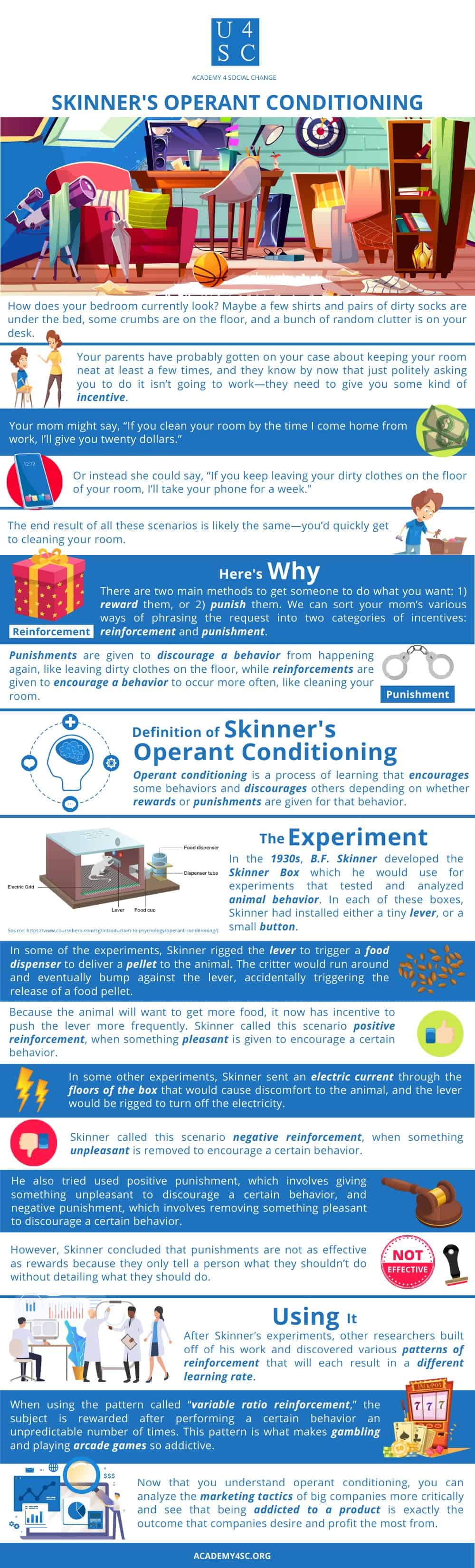

How does the inside of your bedroom currently look? Maybe a few shirts and pairs of dirty socks are placed out of sight under the bed, some crumbs are on the floor from that sandwich you ate while trying to finish your homework at the same time, and a bunch of random clutter is on your desk that you swore you’d organize but never found time to actually do. Your parents have probably gotten on your case about keeping your room neat at least a few times, and they know by now that just politely asking you to do it isn’t going to work—they need to give you some kind of incentive. Here’s a few ways they might phrase their request.

Your mom might say, “If you clean your room by the time I come home from work, I’ll give you twenty dollars.”

Or she might say, “If you clean your room by the time I come home from work, you won’t have to do the dishes after dinner.”

Or maybe she’d say, “If you keep leaving your dirty clothes on the floor of your room, we are going to have a very long talk, and I guarantee it won’t be pleasant!”

Or instead she could say, “If you keep leaving your dirty clothes on the floor of your room, I’ll take your phone for a week.”

The end result of all these scenarios is likely the same—you’d quickly get to cleaning your room. However, can you detect the subtle differences in the kinds of incentives that your mom gives you in each scenario?

Here’s Why

From your personal experience, you’ve probably already discovered that there are two main methods to get someone to do what you want: 1) reward them, or 2) punish them. If we apply this basic idea to the example case where your mom is trying to make you clean your room, we can sort her various ways of phrasing the request into two categories of incentives: reinforcement and punishment.

In the first scenario, your mom is giving something desirable to you—twenty dollars—to encourage you to clean your room. In the second scenario, your mom is taking something undesirable away from you—the chore of washing the dishes—to also encourage you to clean your room. These two scenarios can both be classified as reinforcements, or rewards.

Meanwhile, in the third scenario, your mom is threatening to give something undesirable to you—a long, unpleasant lecture—to discourage you from leaving your room messy. In the fourth scenario, your mom is threatening to take something desirable away from you—your phone—to discourage you from leaving your room messy. These two scenarios can be grouped together as punishments. You might have noticed that your mom’s goal in these last two scenarios is slightly different from her goal in the first two scenarios: punishments are given to discourage a behavior from happening again, like leaving dirty clothes on the floor of your bedroom, while reinforcements are given to encourage a behavior to occur more often, like cleaning your room.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is a process of learning that encourages some behaviors and discourages others depending on whether rewards or punishments are given for that behavior.

The History

F. Skinner was a psychologist who belonged to a school of thought called behaviorism, which posited that studying people’s actions is a more effective way to understand the inner workings of the mind than directly inspecting the mind itself. Thus, in the 1930s, Skinner developed a piece of lab equipment now known as a Skinner Box which he would use for experiments that tested and analyzed animal behavior. In each of these boxes, Skinner had installed either a tiny lever, if it was meant to house a rat, or small button, if it was meant to house a pigeon.

In some of the experiments, Skinner rigged the lever or button in each of the boxes to trigger a nearby food dispenser to deliver a pellet to the animal through an opening in the wall. Immediately after each animal was placed inside its box, the critter would run around exploring its new home and eventually bump against the lever or button, accidentally triggering the release of a food pellet. Because the animal will want to get more food, it now has incentive to push the lever or button more and more frequently. Skinner called this scenario positive reinforcement, in which something pleasant is given to encourage a certain behavior - in this case, the behavior is hitting the lever or button. In some other experiments, Skinner sent an electric current through the floors of the boxes that would cause discomfort to the animal as it scurried around, and the lever or button would be rigged to turn off the electricity. Skinner called this scenario negative reinforcement, in which something unpleasant is removed to encourage a certain behavior - in this case, that behavior is also hitting the lever or button.

Skinner also conducted a few experiments in which he introduced punishments to the animals. When using positive punishment, which involves giving something unpleasant to discourage a certain behavior, Skinner would rig the levers and buttons to set off an electric shock whenever the animal pushed them so that the animal would eventually avoid touching the levers and buttons at all costs. When using negative punishment, which involves removing something pleasant to discourage a certain behavior, Skinner would reduce the amount of daily food pellets given to the animals each time they pressed the lever or button. This also resulted in the animal eventually ceasing to press the levers and buttons. Overall, however, Skinner concluded that punishments are not as effective as rewards in controlling someone’s behavior because punishments only tell the person what they shouldn’t do without specifically detailing what is the proper thing they should do.

Applying It

After Skinner’s experiments, other researchers built off of his work and discovered various patterns of reinforcement that will each result in a different learning rate as well as a different rate of abandoning the behavior after rewards are no longer given. When using the pattern called “variable ratio reinforcement,” the subject is rewarded after performing a certain behavior an unpredictable number of times. This reinforcement pattern is actually what makes gambling and playing certain arcade games so addictive - after a player wins some cash or a stuffed animal prize, they have no idea when they’re going to hit the jackpot again, but still play the same game over and over in hopes that the next try will bring in another big win. Now that you understand operant conditioning, you can analyze the marketing tactics of big companies more critically and see that although being addicted to a product is harmful for the customer, that’s exactly the outcome that companies desire and profit the most from.

Although production companies employ their knowledge of operant conditioning to get people hooked onto harmful, addictive behaviors, many other institutions use operant conditioning to instill positive habits into people. Many employees in the education system are taught techniques based on operant conditioning to help them discipline unruly students as well as children with special needs who may have difficulty following instructions and developing control over their verbal and motor skills. Similar operant conditioning tactics are sometimes employed in prisons or rehabilitation centers to help break cycles of negative behavior and encourage new, healthy habits.