Introduction

Layla’s teacher assigns her class a lot of homework. One day, they give so much that Layla suggests the whole class protest by not doing it, to show their teacher that it is unfair. She’s relying on other members of the class to stick with her, because if they do it, and Layla’s the only one who hasn’t, she will be in trouble, and the teacher will likely ignore her protest. Hopefully, when her teacher sees that no student has done the homework, they will realize that they gave too much and rethink the amount they assign.

Explanation

In 1955 Alabama, African Americans were forced to sit in the back of the bus, even if there was unused space in the front. The police arrested activist Rosa Parks for refusing to give up her seat to a white bus rider, and, as a response to her arrest, tens of thousands of Black bus riders decided to boycott the bus system. By refusing to use the buses, they denied the bus company considerable profit and showed the city that the segregated seating policies were unfair.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted from December 5, 1955, until December 20, 1956. For over a year, tens of thousands of African Americans refused to ride the buses and either walked, cycled, drove, or carpooled with other protesters. The city did not agree to the demands of the protesters, and the segregated seating policies were only discarded when the Supreme Court ruled that they were unconstitutional, a ruling which created lasting effects throughout the country.

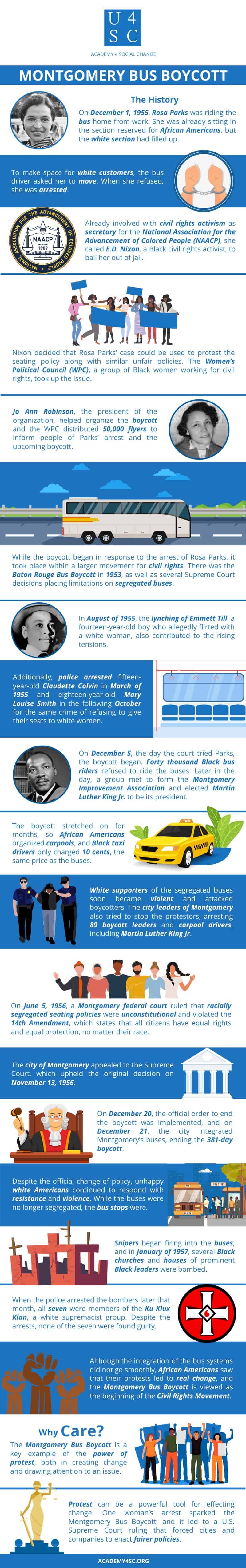

The History

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was riding the bus home from work. She was already sitting in the section reserved for African Americans, but the white section had filled up. To make space for white customers, the bus driver asked her to move. When she refused, she was arrested. Already involved with civil rights activism as secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), she called E.D. Nixon, a Black civil rights activist, to bail her out of jail.

Nixon decided that Rosa Parks’ case could be used to protest the seating policy along with similar unfair policies. The Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of Black women working for civil rights, took up the issue. Jo Ann Robinson, the president of the organization, helped organize the boycott and the WPC distributed 50,000 flyers to inform people of Parks’ arrest and the upcoming boycott.

While the boycott began in response to the arrest of Rosa Parks, it took place within a larger movement for civil rights. There was the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott in 1953, as well as several Supreme Court decisions placing limitations on segregated buses. In August of 1955, the lynching of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old boy who allegedly flirted with a white woman, also contributed to the rising tensions. Additionally, police arrested fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin in March of 1955 and eighteen-year-old Mary Louise Smith in the following October for the same crime of refusing to give their seats to white women, similarly to Rosa Parks.

On December 5, the day the court tried Parks, the boycott began. Forty thousand Black bus riders refused to ride the buses. Later in the day, a group met to form the Montgomery Improvement Association and elected Martin Luther King Jr. to be its president. The boycott stretched on for months, so African Americans organized carpools, and Black taxi drivers only charged 10 cents for their fare, the same price as the buses. White supporters of the segregated buses soon became violent and attacked boycotters. The city leaders of Montgomery also tried to stop the protestors, arresting 89 boycott leaders and carpool drivers, including Martin Luther King Jr.

On June 5, 1956, a Montgomery federal court ruled that racially segregated seating policies were unconstitutional and violated the 14th Amendment, which states that all citizens have equal rights and equal protection, no matter their race. The city of Montgomery appealed to the Supreme Court, which upheld the original decision on November 13, 1956. On December 20, the official order to end the boycott was implemented, and on December 21, the city integrated Montgomery’s buses, ending the 381-day boycott.

Despite the official change of policy, unhappy white Americans continued to respond with resistance and violence. While the buses were no longer segregated, the bus stops were. Snipers began firing into the buses, and in January of 1957, several Black churches and the houses of prominent Black leaders were bombed. When the police arrested the bombers later that month, all seven were members of the Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist group. Despite the arrests, none of the seven were found guilty.

Although the integration of the bus systems did not go smoothly, the Montgomery Bus Boycott drew nationwide attention and led to a monumental legal reform. African Americans saw that their protests led to real change, and this boycott is sometimes viewed as the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. This boycott further served to shine a spotlight on Martin Luther King Jr., who would go on to play an even larger role in the Civil Rights Movement.

Why Care?

The Montgomery Bus Boycott is a key example of the power of protest, both in creating change and drawing attention to an issue. While the boycott lasted almost thirteen months, tens of thousands of African Americans banded together and refused to ride the buses, enduring heat, rain, and violence. Protest, especially protest that involves thousands of people, can be a powerful tool for effecting change. One woman’s arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and it led to a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that forced cities and companies to enact fairer policies.