The Problem

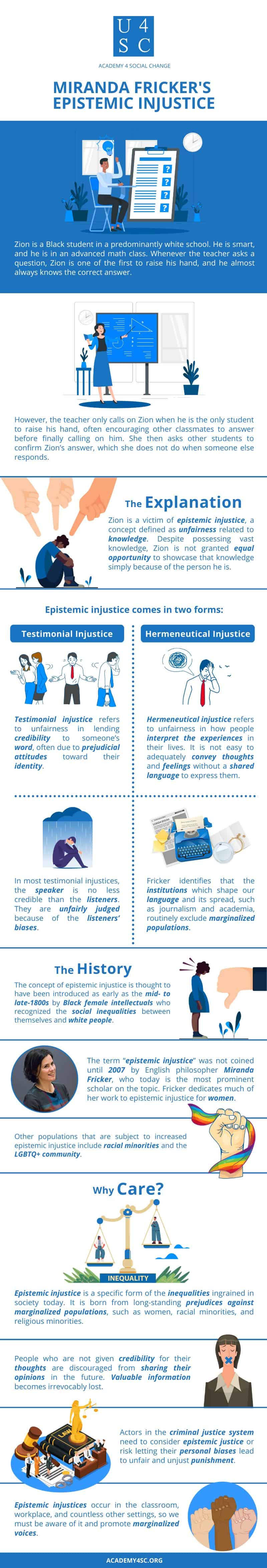

Zion is a Black student in a predominantly white school. He is incredibly smart, and he is in an advanced math class with students older than him. Whenever the teacher asks a question to the class, Zion is one of the first to raise his hand, and he almost always knows the correct answer. However, the teacher only calls on Zion when he is the only student to raise his hand, often encouraging other classmates to answer before finally calling on him. She then asks other students to confirm Zion’s answer, which she does not do when someone else responds.

The Explanation

Zion is a victim of epistemic injustice, a concept broadly defined as unfairness related to knowledge. Despite possessing vast knowledge of the course material, Zion is not granted equal opportunity to showcase that knowledge simply because of the person he is. A subject pioneered by philosopher Miranda Fricker, epistemic injustice comes in two forms: testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice.

Testimonial Injustice

Testimonial injustice refers to unfairness in lending credibility to someone’s word, often due to prejudicial attitudes toward their identity. People sometimes take someone’s opinions less seriously simply because of the person they are. For example, a business manager might disregard a female employee’s suggestions because he is biased against women, or a sports team might select a white player to be their captain over a black player because the coach holds racist attitudes. In most testimonial injustices, the speaker is no less credible than the listeners. They are unfairly judged because of the listeners’ biases.

Hermeneutical Injustice

Hermeneutical injustice refers to unfairness in how people interpret the experiences and events in their lives. It is not easy to adequately convey thoughts and feelings without shared language to express them. A lack of terminology thus leads to a lack of internal and external understanding. Fricker identifies that the institutions which shape our language and its spread, such as journalism and academia, routinely exclude marginalized populations. Thus, she argues, the vocabulary to comprehend these communities is extremely limited, contributing to further hermeneutical injustices. Fricker offers an illustrative example of the term “sexual harassment,” which only came into popular use in the 1970s. Before that, people who were sexually harassed did not have a category for these experiences. Understanding and then communicating their experiences was unfairly difficult, which made it especially challenging to address the issue at hand.

The History

The concept of epistemic injustice is thought to have been introduced as early as the mid- to late-1800s by Black female intellectuals who recognized the social inequalities between themselves and white people. The term “epistemic injustice” was not coined until 2007 by English philosopher Miranda Fricker, who today is the most prominent scholar on the topic. Fricker dedicates much of her work to epistemic injustice for women, who experience diminished capacity as “knowers” in a male-dominated society. Other populations that are subject to increased epistemic injustice include racial minorities and the LGBTQ+ community.

Why Care?

Epistemic injustice is a specific form of the inequalities ingrained in society today. It is born from long-standing prejudices against marginalized populations, such as women, racial minorities, and religious minorities. Epistemic injustice is damaging to the individual victims and to society at large. People who are not given credibility for their thoughts are discouraged from sharing their opinions in the future. Valuable information becomes irrevocably lost. Similarly, without the proper words to describe experiences, how do we identify and address suffering or normalize essential identities?

For these reasons, it is vital to recognize epistemic injustices and encourage marginalized individuals to share their knowledge. These injustices can lead to lasting harm. Actors in the criminal justice system need to consider epistemic justice or risk letting their personal biases lead to unfair and unjust punishment. Epistemic injustices occur in the classroom, workplace, and countless other settings, so we must be aware of it and promote marginalized voices.