Introduction

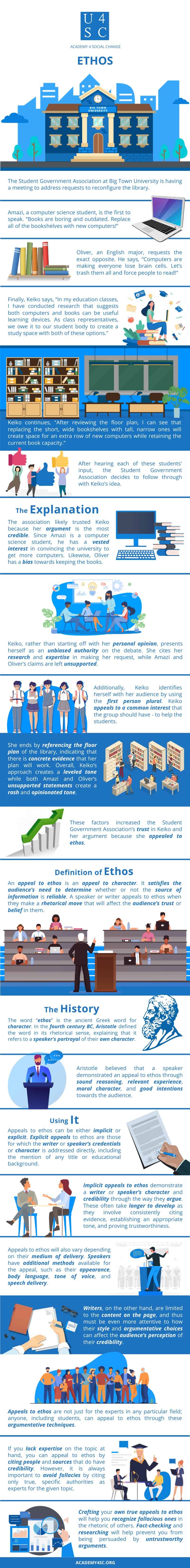

The Student Government Association at Big Town University is having a meeting to address requests to reconfigure the library.

Amazi, a computer science student, is the first to speak. “Books are boring and outdated. Replace all of the bookshelves with new computers!” Oliver, an English major, requests the exact opposite. He says, “Computers are making everyone lose brain cells. Let’s trash them all and force people to read!”

Finally, Keiko says, “In my education classes, I have conducted research that suggests both computers and books can be useful learning devices. As class representatives, we owe it to our student body to create a study space with both of these options. After reviewing the floor plan, I can see that replacing the short, wide bookshelves with tall, narrow ones will create space for an extra row of new computers while retaining the current book capacity.”

After hearing each of these students' input, the Student Government Association decides to follow through with Keiko’s idea.

Explanation

The association likely trusted Keiko because her argument is the most credible. Since Amazi is a computer science student, he has a vested interest in convincing the university to get more computers. Likewise, Oliver has a bias towards keeping the books. Keiko, rather than starting off with her personal opinion, presents herself as an unbiased authority on the debate. She cites her research and expertise in making her request, while Amazi and Oliver’s claims are left unsupported.

Additionally, Keiko identifies herself with her audience by using the first person plural. Keiko appeals to a common interest that the group should have - to help the students. She ends by referencing the floor plan of the library, indicating that there is concrete evidence that her plan will work. Overall, Keiko’s approach creates a leveled tone while both Amazi and Oliver’s unsupported statements create a rash and opinionated tone. These factors increased the Student Government Association’s trust in Keiko and her argument because she appealed to ethos.

Definition of Ethos

An appeal to ethos is an appeal to character. It satisfies the audience’s need to determine whether or not the source of information is reliable. A speaker or writer appeals to ethos when they make a rhetorical move that will affect the audience’s trust or belief in them, whether that be personally or as a source of information on the topic at hand.

The History

The word “ethos” is the ancient Greek word for character. In the fourth century BC, Aristotle defined the word in its rhetorical sense, explaining that it refers to a speaker's portrayal of their own character. Aristotle believed that a speaker demonstrated an appeal to ethos through sound reasoning, relevant experience, moral character, and good intentions towards the audience. Over time, the meaning has broadened to include more possible aspects such as a rhetorician’s authority, trustworthiness, expertise, and level of similarity to the audience.

Using It

Appeals to ethos can be either implicit or explicit. Explicit appeals to ethos are those for which the writer or speaker’s credentials or character is addressed directly, including the mention of any title or educational background. These credentials allow someone to lay claim to a certain level of authority or expertise on a given topic. Implicit appeals to ethos, on the other hand, demonstrate a writer or speaker’s character and credibility through the way they argue. These appeals often take longer to develop as they can involve consistently citing evidence, establishing an appropriate tone, and proving trustworthiness through consideration of alternative views.

Appeals to ethos will also vary depending on their medium of delivery. Speakers have additional methods available for the appeal, such as their appearance, body language, tone of voice, and speech delivery. Writers, on the other hand, are limited to the content on the page, and thus must be even more attentive to how their style and argumentative choices can affect the audience’s perception of their credibility.

Appeals to ethos are not just for the experts in any particular field; anyone, including students, can appeal to ethos through these argumentative techniques. If you lack expertise on the topic at hand, you can appeal to ethos by citing people and sources that do have credibility. However, it is always important to avoid fallacies by citing only true, specific authorities as experts for the given topic. Crafting your own true appeals to ethos will help you recognize fallacious ones in the rhetoric of others. Fact-checking and researching will help prevent you from being persuaded by untrustworthy arguments.