Introduction

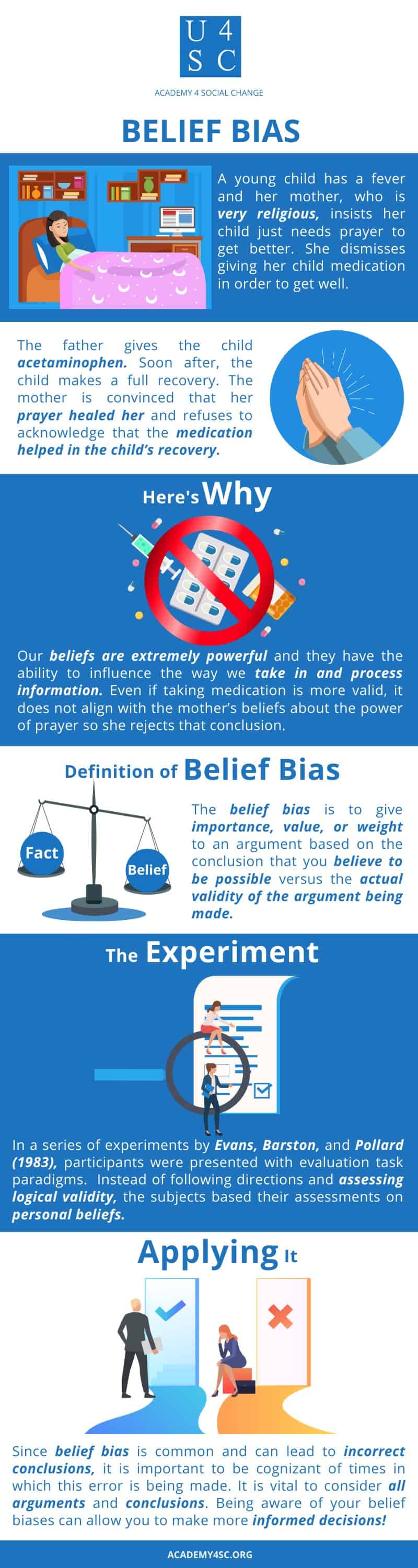

Consider the following scenario. A young child has a fever and her mother, who is very religious, insists her child just needs prayer to get better. She completely dismisses the possibility of giving her child medication in order to get well. On the other hand, the father does not agree with the mother and gives the child acetaminophen. Soon after she takes the medication, the child makes a full recovery. While the mother is convinced that her prayer allowed her daughter to bounce back from her illness, she refuses to acknowledge that the medication might have played a role in the child’s recovery.

Explanation

Our beliefs are extremely powerful. So powerful that they have the ability to greatly influence the way we take in and process information. When an argument is being made, there are conclusions that we give more value to due to our personal beliefs. One argument is valued over another because it is being used to support a conclusion that you desire. This can mean that if we agree with a view, we are more likely to support any data and information that supports that viewpoint. Due to her personal religious beliefs, the girl’s mother believes that her daughter recovered due to prayer and does not consider the alternative argument, which is that the medication helped her feel better. Even if the alternative explanation is more valid, it does not align with the mother’s beliefs about the power of prayer, and therefore, she rejects that conclusion.

Belief Bias

The belief bias is to give importance, value, or weight to an argument based on the conclusion that you believe to be possible versus the actual validity of the argument being made.

Experiment

In a series of experiments by Evans, Barston, and Pollard (1983), participants were presented with evaluation task paradigms, containing two premises and a conclusion. The participants were asked to make an evaluation of logical validity. The subjects, however, exhibited a belief bias, evidenced by their tendency to reject valid arguments with unbelievable conclusions, and endorse invalid arguments with believable conclusions. Instead of following directions and assessing logical validity, the subjects based their assessments on personal beliefs.

Applying It

Since belief bias is extremely common and can lead one to reach incorrect conclusions, it is important to try to be cognizant of times in which this error is being made. It is vital to consider all arguments and conclusions, whether or not they align with our personal beliefs. For example, people registered within a certain political party tend to jump to conclusions when listening to a politician from the opposing party makes an argument. Oftentimes the person is not considering the validity of the argument but is instead convinced the politician making the argument is wrong because they disagree with the conclusion of the argument. This idea that the argument is incorrect is solely based on the individual’s personal beliefs and has little to do with the actual argument. For this reason, it is important to consider how our beliefs are impacting our day to day decisions and thoughts. Being aware of your belief biases can allow you to make more informed decisions!