Have You Ever?

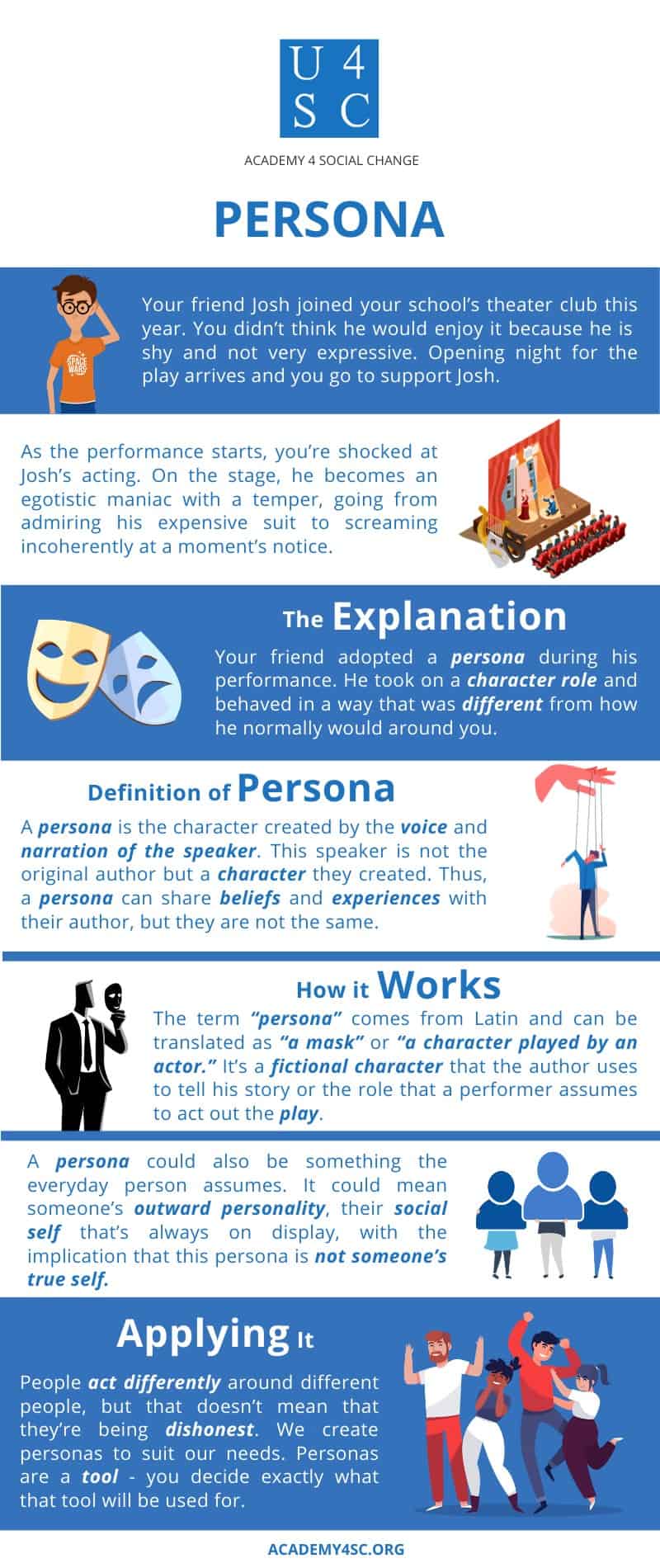

Let’s say your friend Josh joined your school’s theater club this year. You didn’t think he would enjoy it: Josh is friendly but very shy and not very expressive. He rarely speaks, and you’ve never heard him raise his voice above a whisper even when he’s angry. Opening night for the play arrives and you go to support Josh. As the performance starts, you’re shocked at Josh’s casting. Not only did he get a supporting role, but he’s also acting very differently from his usual self. On the stage, he becomes an egotistic maniac with a temper, going from admiring his expensive suit to screaming incoherently at a moment’s notice.

Here’s Why

Your friend adopted a persona during his performance. He took on a character role and behaved in a way that was different from how he normally would around you.

Persona

A persona is, simply put, a character. In literature, a persona is the character created by the voice and narration of the speaker. This speaker is not the original author but a character they created. Thus, a persona can share similar beliefs and experiences with their author, but they are not one and the same.

The History

The term “persona” comes from Latin and can be translated as “a mask” or “a character played by an actor.” It was first used in the mid eighteenth century when discussing literary works. A persona is an assumed role that either an author or performer adopts. It’s a fictional character the author uses to tell his story or the role that a performer assumes to act out the play. In theater, the personas displayed by actors will appear on a list of all assumed characters called the dramatis personae. The persona an author adopts in poetry is characterized through narration and the voice of the piece.

The word “persona” received limited use until the twentieth century when it gained a broader definition. Rather than be confined to just the stage and written text, a persona could be something the everyday person assumed. A persona could mean someone’s outward personality, their social self that’s always on display, with the implication that this persona is not someone’s true self. This more general definition became popular in no small part because of its use in psychology and now is used just as frequently as its original one.

So What

It’s important to remember that a narrator doesn’t always reflect the views of the author. Just because a work contains what you know to be a true experience the author had doesn’t mean the narrator and author are interchangeable. Using a persona with similar experiences or beliefs can help writers ground their piece or provoke an emotional reaction from the reader.

Actors, celebrities, and even politicians have personas too and wear them for similar reasons. While personas function as a kind of mask, this doesn’t mean that everyone who has one is lying. Rather, people have reasons for wearing those masks - to entertain an audience, be taken more seriously by voters, and so on.

People act differently around different people, but that doesn’t mean that they’re being dishonest. Instead of getting caught up in the search for what’s “true”, sometimes it’s better to remember that a person’s behavior influences others. Ask yourself, “what does this persona help them gain?” We create personas to suit these needs. Sometimes these personas are created dishonestly and expressly with the purpose to trick others, but this doesn’t make personas intrinsically bad. Personas are a tool - you decide exactly what that tool will be used for.